When M.R. James’ Ghost Stories of an Antiquary appeared in 1904, readers were puzzled to find that it contained only four illustrations, an odd number for a book of eight stories. In the preface, James explained that he’d assembled the collection at the suggestion of a friend who had offered to illustrate it but was “taken away” unexpectedly after completing only four pictures.

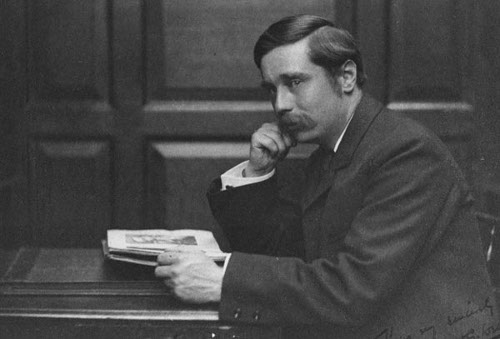

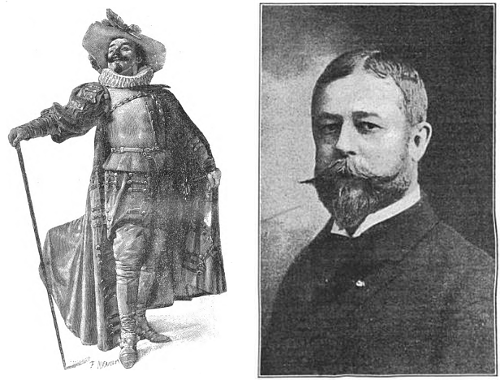

The friend was James McBryde, a student whom James had met in 1893 at King’s College, Cambridge, where James was dean. The two quickly became close, and McBryde was one of the select few to whom James would read a new ghost story each Christmas by the light of a single candle. They remained close after McBryde left Cambridge, traveling together each year to Denmark and Sweden, and eventually they appointed to work together to publish the ghost stories, which now numbered enough for a collection.

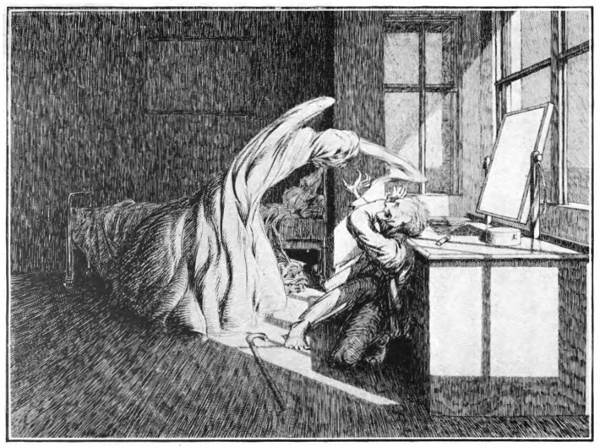

In May 1904 McBryde wrote, “I don’t think I have ever done anything I liked better than illustrating your stories. To begin with I sat down and learned advanced perspective and the laws of shadows …” Regarding the collection’s crowning horror, “Oh, Whistle, and I’ll Come to You, My Lad,” he wrote, “I have finished the Whistle ghost … I covered yards of paper to put in the moon shadows correctly and it is certainly the best thing I have ever drawn.”

Alas, McBryde died only a month later of complications following an appendix operation. James was adamant that no replacement be found, and Ghost Stories of an Antiquary was published with only four illustrations as a tribute to his friend. “Those who knew the artist will understand how much I wished to give a permanent form even to a fragment of his work,” he wrote. “Others will appreciate the fact that here a remembrance is made of one in whom many friendships centred.”

Of the true depth of their friendship, the full story will never be known. James picked roses, lilac, and honeysuckle from the Fellows Garden at King’s College and carried them with him on the train to McBryde’s funeral in Lancashire, where he dropped them into the grave after the other mourners had left. He remained friends with McBryde’s wife and legal guardian of his daughter, and he arranged for the posthumous publication of McBryde’s children’s book The Story of a Troll Hunt. In the introduction he wrote, “The intercourse of eleven years, — of late, minutely recalled, — has left no single act or word of his which I could choose to forget.”