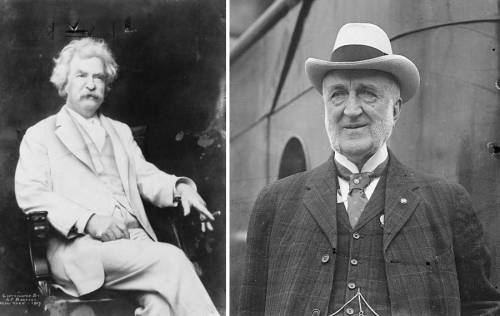

Traveling on the same ship, Mark Twain and Chauncey Depew were asked to address the dinner crowd. Twain went first and spoke for 20 minutes to great applause. Then Depew rose.

“Mr. Toastmaster and ladies and gentlemen,” he said, “before this dinner, Mark Twain and I made an agreement to trade speeches. He has just delivered my speech, and I thank you for the pleasant manner in which you received it. I regret to say that I have lost the notes of his speech and cannot remember anything he has to say.” And he sat down, to much laughter.

The next day, an Englishman found Twain in the smoking room. “Mr. Clemens,” he said, “I consider you were much imposed on last night. I have always heard that Mr. Depew is a clever man — but really, that speech of his you made last night struck me as being most infernal rot.”