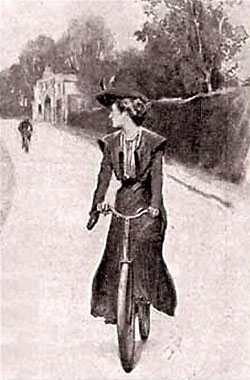

In the Sherlock Holmes story “The Adventure of the Solitary Cyclist,” Arthur Conan Doyle created an inadvertent grammatical puzzle: Who does the term “solitary cyclist” refer to? Apart from the title, the phrase appears only twice in the story:

- “I will now lay before the reader the facts connected with Miss Violet Smith, the solitary cyclist of Charlington, and the curious sequel of our investigation, which culminated in unexpected tragedy.”

- “‘That’s the man!’ I [Watson] gasped. A solitary cyclist was coming towards us. His head was down …”

The first passage describes a woman and the second a man, Bob Carruthers. Which is the solitary cyclist of the title? For 69 years Holmes fans debated the question. Those who argued for Smith read “the solitary cyclist of Charlington” as an appositive phrase, another name for “Miss Violet Smith.” Certainly Carruthers was “a” solitary cyclist, but “the” solitary cyclist was Smith.

Those who argued for Carruthers thought that “the solitary cyclist of Charlington” above was not a description of Smith but the second item in a list — that is, Watson was promising to describe three things: the facts of the case, the cyclist, and the sequel. They allowed, though, that the comma after that phrase was unusual (I gather that the serial comma wasn’t commonly used then). In the story Carruthers pursues Smith, both on bicycles, so either interpretation seems reasonable.

The matter was resolved in 1972, when Andrew Peck tracked down the original manuscript in Cornell University’s rare book room. In the title and in the first passage above Doyle had originally written “man” and then crossed it out and substituted “cyclist.” So the solitary cyclist is definitely Bob Carruthers. Another mystery solved!

(Andrew J. Peck, “The Solitary Man-uscript,” Baker Street Journal, June 1972.)