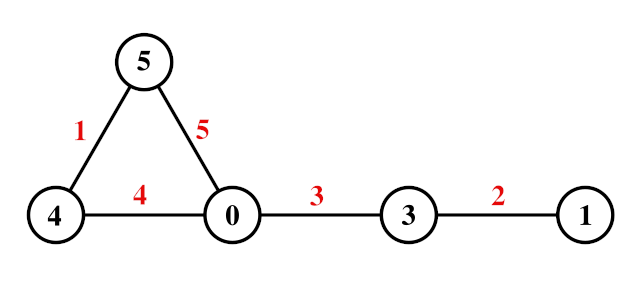

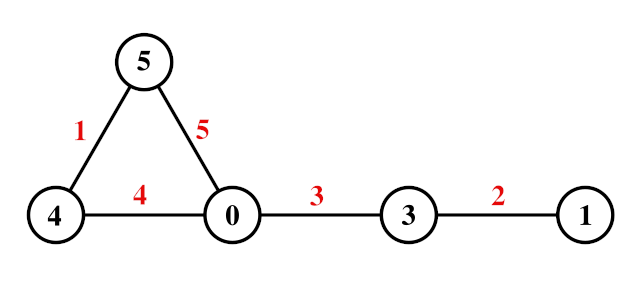

This graph has 5 edges, and we’ve managed to label its vertices in a remarkable way: Each vertex bears some integer from 0 to 5, no two receive the same integer, and each edge is now uniquely identified by the absolute difference between its endpoints, such that this magnitude lies between 1 and 5 inclusive. Such a labeling is called graceful.

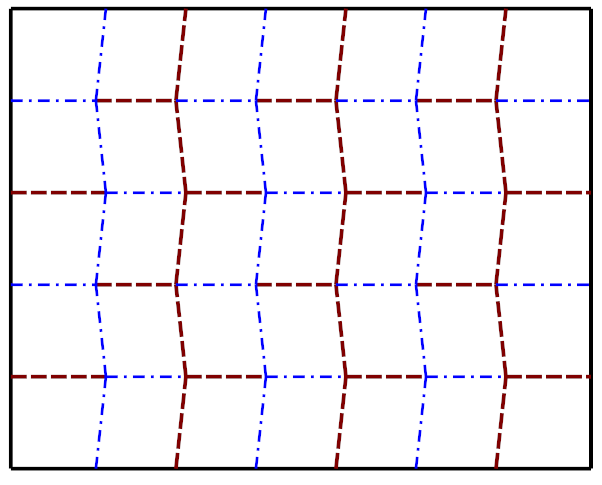

In 2008 Donald E. Knuth made a graph representing the contiguous 48 states and the District of Columbia in which each pair of states are connected if they’re joined by at least one drivable road. It turns out that this graph can be labeled gracefully.

And, amazingly, in 2020 T. Rokicki discovered that if you undertake an imaginary journey on Knuth’s map, starting in California and going up the Pacific coast and then along the Canadian border, you’ll visit successive vertices labeled 31, 41, 59, 26, 53, 58, 97, 93, 23, 84, 62, 64, 33, 83, and 27. These are the first 30 decimal digits of π!

Knuth called this a “graceful miracle.”