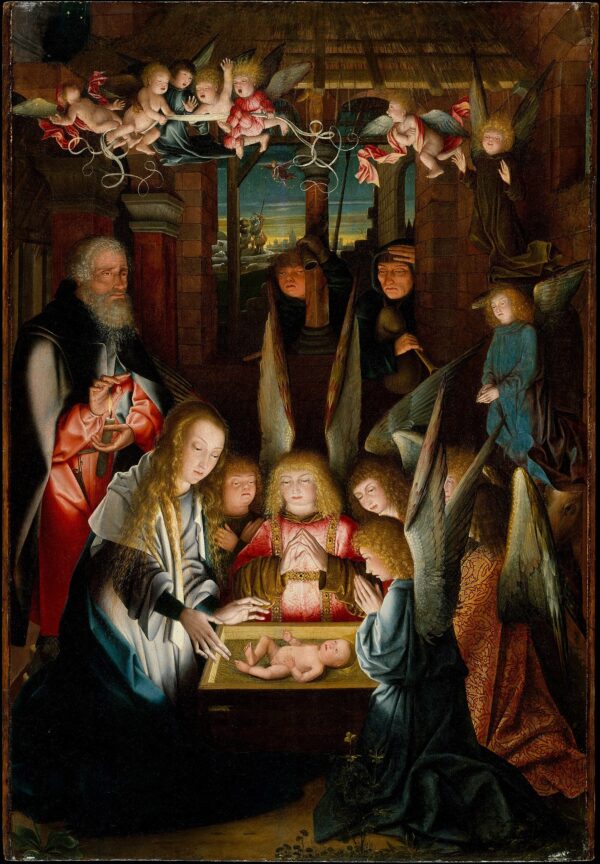

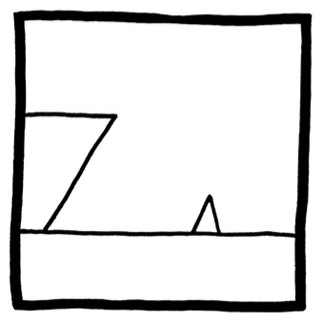

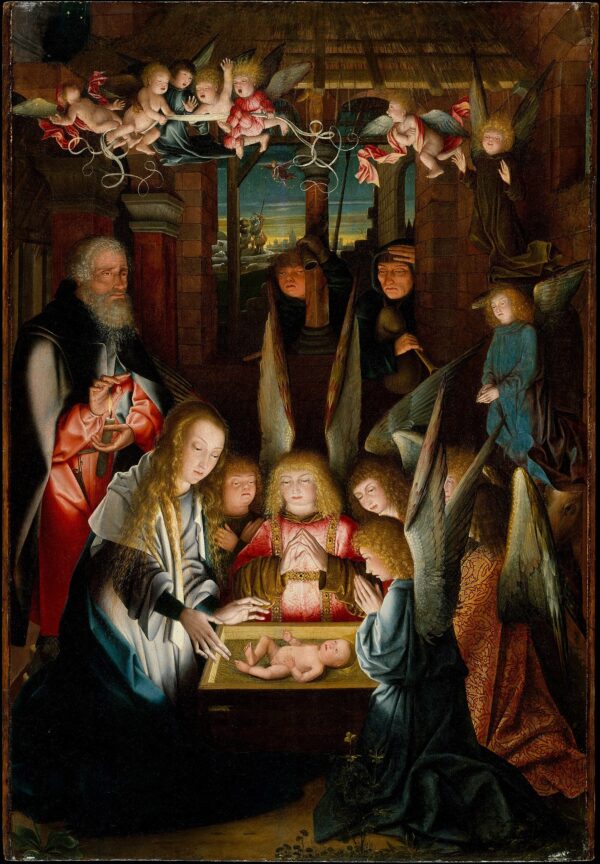

In this 1515 painting, The Adoration of the Christ Child, the angel immediately to Mary’s left appears to bear the characteristic facial features of Down syndrome (click to enlarge). This would make the painting one of the earliest representations of the syndrome in Western art.

Unfortunately, little is known about it. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, which owns it, has identified the painter only as a “follower of Jan Joest of Kalkar.” Researchers Andrew Levitas and Cheryl Reid have suggested that the painting may indicate that individuals with Down syndrome were not regarded as disabled in medieval society. But so little is known about the work or its creator that it’s hard to establish a reliable conclusion.

“After all the speculations, we are left with a haunting late-medieval image of a person with apparent Down syndrome with all the accouterments of divinity. It is impossible to know whether any disability had been recognized or whether it simply was not relevant in that time and place.”

(Andrew S. Levitas and Cheryl S. Reid, “An Angel With Down Syndrome in a Sixteenth Century Flemish Nativity Painting,” American Journal of Medical Genetics Part A 116:4 [2003], 399-405.) (Thanks, Serge.)