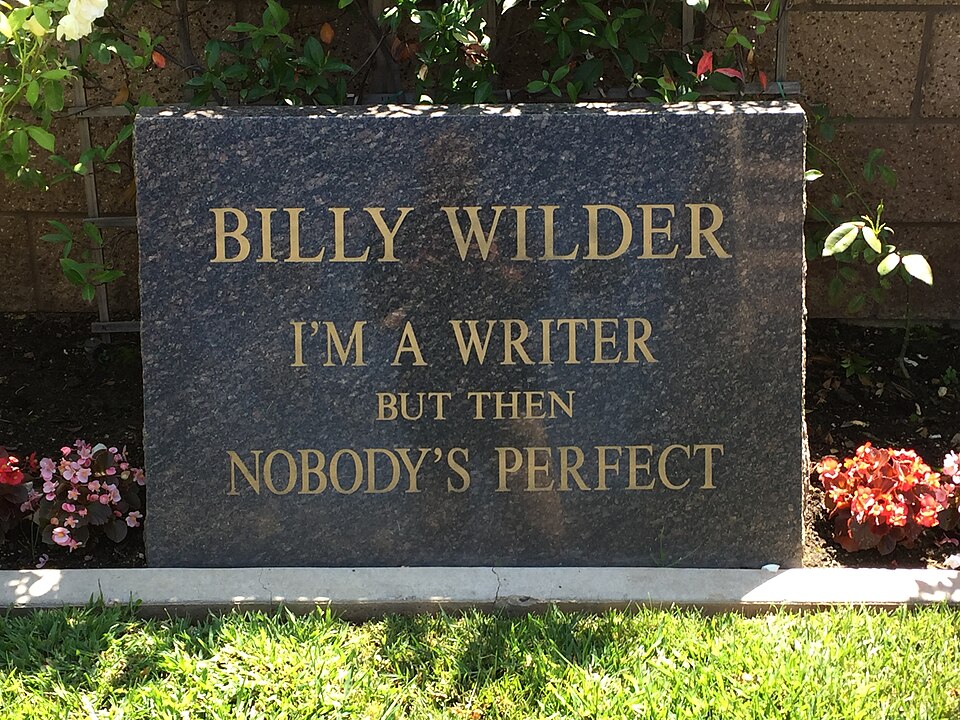

Billy Wilder’s grave, Westwood Village Memorial Park Cemetery, Los Angeles:

Billy Wilder’s grave, Westwood Village Memorial Park Cemetery, Los Angeles:

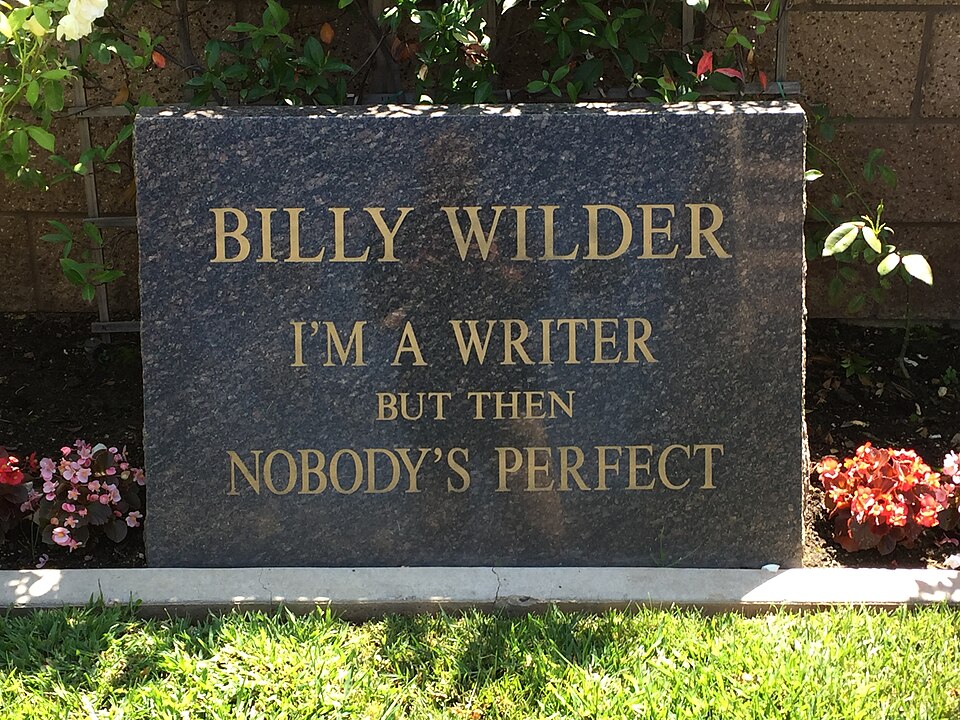

From the Strand, December 1901, “one of Sir John Stainer’s musical jokes, two hymns in one — in B flat or G major, according to the manner in which it is read, upside up or upside down. It was written as an autograph for a friend of his son’s.”

When James Cameron was serving as second unit director on Galaxy of Terror (1981), he was asked to film an insert of a severed arm that’s being eaten by maggots. The team made a fake arm, covered it with mealworms, lit the shot, and rolled the camera, but the mealworms didn’t move. “They looked completely inert,” Cameron said. “So I thought, well, what would happen if we put a little electrical current through these worms? Maybe they’d jump around a little more.

“So we get all ready to do the shot and two guys I knew who were producers had come up behind me to watch me work because they had heard I was doing some directing. I rolled the camera and when I said ‘Action,’ what they saw was two hundred mealworms all come to life. When I said ‘Cut,’ they stopped moving.

“This must have been tremendously impressive to two low-budget horror-movie producers. I’m sure they ratcheted up in their mind that if I could get a performance out of worms, I probably could work very well with actors.” They hired him that day to direct Piranha II.

(Robert J. Emery, The Directors: Take One, 2002.)

In 2005, Jeremy Winterson bought a bootleg copy of Revenge of the Sith in Shanghai and noticed something wrong with the English subtitles.

The movie’s dialogue had been translated mechanically into Chinese and then translated back again into English, leaving it almost incomprehensible. (A similar disaster had befallen a Portuguese-French phrasebook in 1883.)

Fans replaced the movie’s original audio dialogue with voice actors reading the mistranslated subtitles, and the result is Star War the Third Gathers: Backstroke of the West (highlights above).

This 1904 comic by Gustave Verbeek (click to enlarge) is a sort of visual palindrome — the first six panels are presented conventionally, and then they’re displayed again in reverse order and upside down to compose the story’s second half. Even the written messages change their meaning: why big buns am mad u! becomes in pew we sung big hym, and so on. Only the captions beneath the first panels are discarded in the second half.

A surprising detail from Duke Ellington’s childhood, from his 1973 autobiography Music Is My Mistress:

There were many open lots around Washington then, and we used to play baseball at an old tennis court on Sixteenth Street. President Roosevelt would come by on his horse sometimes, and stop and watch us play. When he got ready to go, he would wave and we would wave at him. That was Teddy Roosevelt — just him and his horse, nobody guarding him.

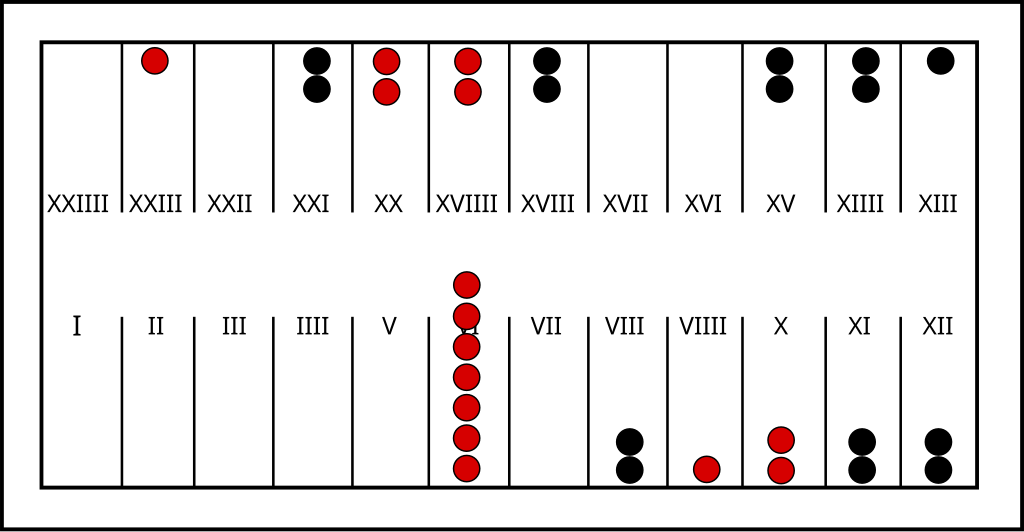

Playing tabula, a forerunner of backgammon, in 480 AD, the Byzantine emperor Zeno made such a stupendously unfortunate dice roll that we still remember it 1500 years later. Playing red in the position above, Zeno rolled a 2, 5, and 6. “As he was unable to move the men on (6) which were blocked by the black men on (8), (11), (12): or the singleton on (9), which was blocked by the black pieces on (11), (14), (15): he was forced to break up his three pairs, a piece from (20) going to (22), one from (19) going to (24), and one from (10) going to (16),” explained R.C. Bell in Board and Table Games From Many Civilizations (1960). “No other moves were possible and he was left with eight singletons and a ruined position.”

See Dice Shaming.

“Instead of saying ‘cut’ at the end of a take, he would say, ‘That’s enough of that shit.’ After your own close-up, it’s hilarious, but when I saw him doing it to himself, it really made me laugh.” — Laura Dern, of Clint Eastwood

Fictitious correspondents invented by T.S. Eliot in kick-starting a letters page in The Egoist in 1917:

The Rev. Charles James Grimble

Muriel A. Schwarz

Charles Augustus Conybeare

Helen B. Trundlett

J.A.D. Spence

Apparently this wasn’t unusual for Eliot, who wrote for The Tyro in 1921 as Gus Krutzsch. When I.A. Richards invited Krutzsch to meet him in Peking, Eliot replied, “I do not care to visit any country which has no native cheese.”

As a hedge against hard times, W.C. Fields used to open bank accounts under assumed names, including Sneed Hearn, Dr. Otis Guelpe, Figley E. Whitesides, and Professor Curtis T. Bascom.

“He had bank accounts, or at least safe-deposit boxes, in such cities as London, Paris, Sydney, Cape Town, and Suva,” said his friend Gene Fowler in 1949. “I do not know this for a fact, but I think that much of his fortune still rests in safe-deposit boxes about which, deliberately or not, he said nothing.”