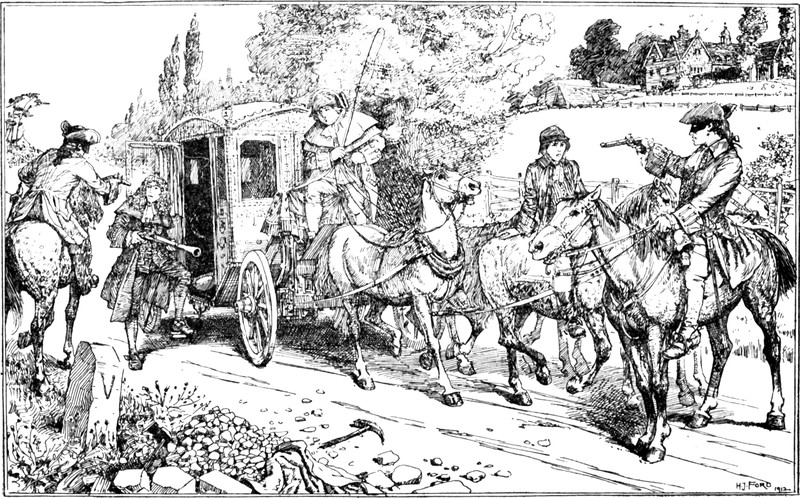

In “Short Notes of My Life,” Horace Walpole records an alarming experience:

One night in the beginning of November, 1749, as I was returning from Holland House by moonlight, about ten at night, I was attacked by two highwaymen in Hyde Park, and the pistol of one of them going off accidentally, razed the skin under my eye, left some marks of shot on my face, and stunned me. The ball went through the top of the chariot, and if I had sat an inch nearer to the left side, must have gone through my head.

After an account of the robbery appeared in the London Evening Post, he received a letter:

Sir: seeing an advertisement in the papers of to Day giveing an account of your being Rob’d by two Highway men on wedensday night last in Hyde Parke and during the time a Pistol being fired whether Intended or Accidentally was Doubtfull Oblidges Us to take this Method of assureing you that it was the latter and by no means Design’d Either to hurt or frighten you for tho’ we are Reduced by the misfortunes of the world and obliged to have Recourse to this method getting money Yet we have Humanity Enough not to take any body’s life where there is Not a Nessecety for it.

The highwayman returned Walpole’s belongings in exchange for the reward that had been offered. He turned out to be James MacLaine, second son of a Scottish Presbyterian minister, who had turned to crime after his wife’s death. Over the course of six months, he and his accomplices committed 20 highway robberies, wearing Venetian masks and treating their victims with courtesy. When MacLaine was captured the following year, Walpole refused to appear against him, and when he was condemned Walpole noted that 3,000 people went to see him in his cell at Newgate.