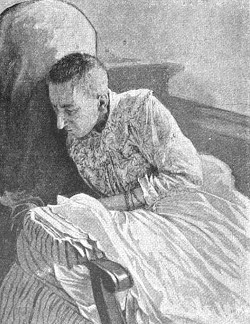

In November 1985, a couple walked into an art museum in Tucson, Arizona. While the woman chatted with a security guard, the man disappeared briefly upstairs, and then the pair departed. Then the guard discovered that Willem de Kooning’s painting Woman-Ochre was missing — it had been cut out of its canvas.

More than 30 years later, in 2017, retired New York speech pathologist Rita Alter passed away in the little town of Cliff, N.M., five years after her husband, Jerry, a former schoolteacher. In their bedroom was the missing de Kooning, in a position that was visible only when the door was closed. The painting appeared to have been reframed only once in the 31 years it had been missing, suggesting that it had had only one owner in that time.

Had the Alters stolen the painting? They were admirers of de Kooning and had been in Tucson the day before the theft. But such a crime seems vastly out of character for the retiring couple. “[They wouldn’t] risk something as wild and crazy as grand larceny — risk the possibility of winding up in prison, for God’s sake — they wouldn’t do that,” Rita’s sister told the New York Times.

Had the pair then bought the painting from a third party? That seems impossible too — it was worth an estimated $160 million. Perhaps the painting’s authenticity had been forgotten by the time of the transaction, so that both buyer and seller thought it was a copy? How could that have come about?

Jerry Alter once published a story in which a woman and her granddaughter steal an emerald from a museum and keep it on private display, “where two pairs of eyes, exclusively, are there to see.” Is that a coincidence? A veiled admission?

We may never know. The FBI’s case remains open.

(Thanks, Daniel.)