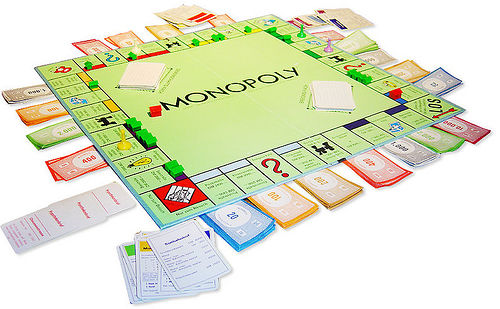

In 1983, East Carolina University mathematicians Thomas Chenier and Cathy Vanderford programmed a computer to find the best strategies in playing Monopoly. The program kept track of each players’ assets and property, and subroutines managed the decisions whether to buy or mortgage property and the results of drawing of Chance and Community Chest cards. They auditioned four basic strategies (I think all of these were in simulated two-player games):

- Bargain Basement. Buy all the unowned property that you can afford, hoping to prevent your opponent from gaining a monopoly.

- Two Corners. Buy property between Pennsylvania Railroad and Go to Jail (orange, red, and yellow), hoping your opponent will be forced to land on one on each trip around the board.

- Controlled Growth. Buy property whenever you have $500 and the color group in question has not yet been split by the two players. Hopefully this will allow you to grow but retain enough capital to develop a monopoly once you’ve acquired one.

- Modified Two Corners. This is the same as Two Corners except that you also buy the Boardwalk-Park Place group.

After 200 simulated games, the winner was Controlled Growth, with 88 wins, 79 losses, and 33 draws. Bargain Basement players tended to lack money to build houses, and Two Corners gave the opponent too many opportunities to build a monopoly and was vulnerable to interference by the opponent, but Modified Two Corners succeeded fairly well. In Chenier and Vanderford’s calculations, Water Works was the most desirable property, followed by Electric Co. and three railroads — B&O, Reading, and Pennsylvania. Mediterranean Ave. was last. Of the property groups, orange was most valuable, dark purple least. And going first yields a significant advantage.

“In order for everyone here to become Monopoly Moguls, we offer the following suggestions: If your opponent offers you the chance to go first, take it. Buy around the board in a defensive manner (that is at least one property per group). When trading begins, trade for the Orange-Red corner as well as for the Lt. Blue properties. They are landed on most frequently and offer the best return. The railroads and utilities offer a good chance for the buyer to raise some cash with which he may later develop other properties. Finally, whenever your opponent has a hotel on Boardwalk, never, we repeat, never land on it.”

(Thomas Chenier and Cathy Vanderford, “An Analysis of Monopoly,” Pi Mu Epsilon Journal 7:9 [Fall 1983], 586-9.)