Artist Michael Kalish spent three years creating this portrait of Muhammad Ali from 1,300 punching bags.

It appeared in the L.A. Live complex in downtown Los Angeles in March 2011.

Artist Michael Kalish spent three years creating this portrait of Muhammad Ali from 1,300 punching bags.

It appeared in the L.A. Live complex in downtown Los Angeles in March 2011.

Typographer John Langdon designed this ambigram for the Department of English & Philosophy at his institution, Drexel University.

“This illusion was a particularly difficult challenge,” he told Brad Honeycutt for The Art of Deception (2014). “My attempts to create more ‘conventional’ (rotational, mirror-image, etc.) ambigrams for these two words were unsuccessful. But my personal investments in both philosophy and language seem to inspire me to some of my best work. This ‘perception shift’ ambigram was very difficult to develop, but my stubborn persistence finally paid off. The two words ‘philosophy’ and ‘English’ can be difficult to discern, but with a little patience and a voluntary perception shift, finding them is particularly satisfying.”

There’s much more at Langdon’s site.

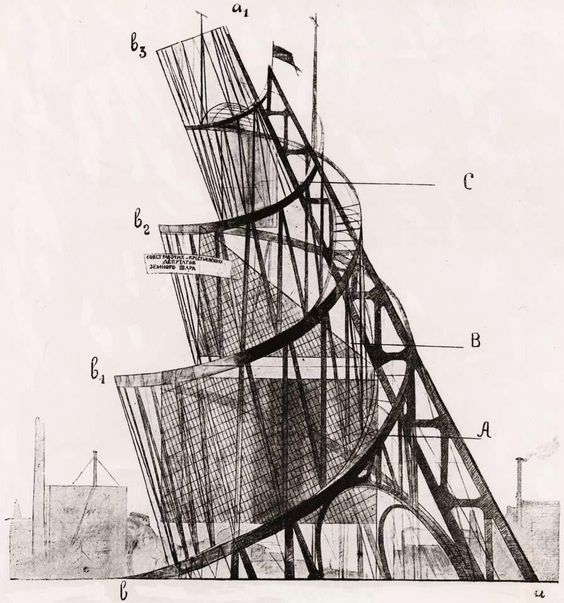

After the Bolshevik Revolution, architect Vladimir Tatlin proposed this enormous monument to house Communist headquarters in Petrograd. Two large helixes would spiral 400 meters into the air, surpassing the Eiffel Tower as the world’s foremost symbol of modernity. The helixes would point to Polaris, so that the star and the tower would remain motionless relative to each other. Suspended from the framework would be three office buildings of glass and steel, each moving in harmony with the cosmos: A is a cylindrical auditorium that rotates once a year, B is a cone-shaped office structure that rotates once a month, C is a cubical information center that rotates once a day, and on top is an open-air screen on which messages could be projected. (During overcast weather they planned to project the news onto clouds.)

In the end it was never built — even if Russia could have produced the steel, it’s not clear that it would have stood up.

In the early 20th century, inspired by the scientific hope that the mind could evolve to ever-higher levels of consciousness, Russian poets tried to paint this higher reality with paradoxical statements that defied common sense. This movement reached its apotheosis in 1913 when Aleksei Kruchenykh wrote “Dyr bul shchyl,” an untranslatable arrangement of letters on a page. Kruchenykh added the legend “3 poems written in my own language different from others: its words do not have a definite meaning.” Kruchenykh named this new language zaum, Russian for transrational, because it transcends common sense and logic.

“For whom was Kruchenykh writing these poems?” asks Lynn Gamwell in Mathematics + Art. “He wrote for other avant-garde poets — he was a poet’s poet — and, according to his late-nineteenth-century biological worldview, the poets in his audience possessed expanded (more highly evolved) minds. Kruchenykh did not communicate in the ordinary sense — he deliberately chose obfuscation, made-up words. He composed his poems to reach a small, elite art audience whose brains, to his way of thinking, had evolved enough to perceive an actual infinity — the Absolute. In other words, the subject matter of his verse was neither nonsense nor an occult realm but rather an alleged higher ‘transrational’ level of reasoning.”

This is an unretouched photo — in 2007 artist Julien Attiogbe took photos of the building at 39 Avenue George V in Paris, distorted them using a computer, then printed the photos on large canvases and applied them to the building’s facade.

At the site where apartheid police officers arrested Nelson Mandela in 1962, sculptor Marco Cianfanelli has erected 50 laser-cut steel columns. They range in height from 21 to 31 feet and appear randomly placed, but the approach to the site leads visitors down a path at the correct angle, and at a distance of 115 feet their meaning becomes clear.

“The fifty columns represent the fifty years since his capture, but they also suggest the idea of many making the whole, of solidarity,” Cianfanelli said in a statement at the sculpture’s dedication in 2012. “It points to an irony as the political act of Mandela’s incarceration cemented his status as an icon of struggle, which helped ferment the groundswell of resistance, solidarity, and uprising, bringing about political change and democracy.”

06/14/2017 UPDATE: I’m told there’s also a scale model of the sculpture at Constitution Hill in Johannesburg, which may be more accessible. (Thanks, Martin.)

06/14/2017 UPDATE: There’s a similar installation on the wall of 105 Rue du Faubourg-Saint-Denis in Paris (below), by artist Jean-Pierre Yvaral, depicting Vincent de Paul, who established a mission here to care for the needy. (Thanks, Nick.)

06/19/2017 UPDATE: And Daniël Hoek noted that a portrait of Steve Jobs is hidden in fence pickets in Lower Manhattan, near Silicon Alley:

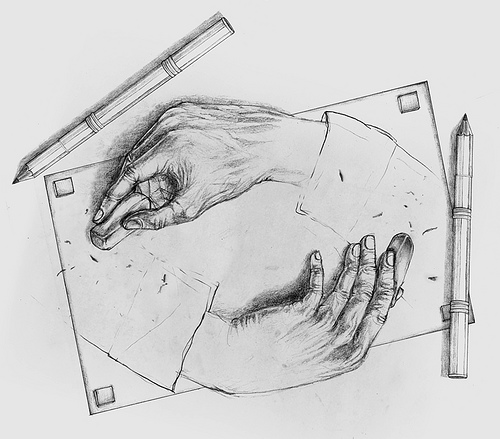

“Erasing Hands,” by Malaysian illustrator Tang Yau Hoong. What happens next?

In 2013, artist Kim Beaton and 25 volunteers constructed a 12-foot papier-mâché “tree troll” with the kindly face of the sculptor’s late father, Hezzie Strombo, a Montana lumberjack.

[My father] had died a few months prior at 80 years old. On June 2nd, at 3am, I woke from a dream with a clear vision burning in my mind. The image of my dad, old, withered and ancient, transformed into one of the great trees, sitting quietly in a forest. I leaped from my bed, grabbed some clay and sculpted like my mind was on fire. In 40 minutes I had a rough sculpture that said what it needed to. The next morning I began making phone calls, telling my friends that in 6 days time we would begin on a new large piece. The next 6 days, I got materials and made more calls. On June 8th we began, and 15 days later we were done. I have never in my life been so driven to finish a piece.

The troll now makes holiday appearances at the Bellagio casino in Las Vegas.

(From My Modern Met.)

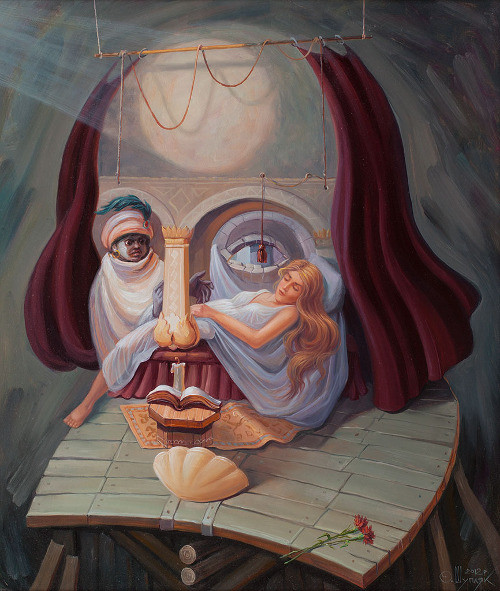

Ukrainian artist Oleg Shuplyak specializes in “Hidden Images,” in which famous faces emerge from simple scenes.

Initially trained as an architect, he’s been a member since 2000 of the National Union of Artists of Ukraine.

Mozart’s expense book for May 27, 1784, contains a curious entry:

Starling bird. 34 kreutzer.

Das war schön!

He had bought a starling on that date, apparently after asking it to repeat the opening theme of the third movement of his Piano Concerto No. 17 in G, K. 453, which he’d completed a few weeks earlier. The bird had held the first G rather long, and then sharped two Gs in the following measure, but Mozart’s exclamation (“That was beautiful!”) shows that he approved.

He kept the bird for three years, until its death on June 4, 1787, when he buried it in his backyard. Then he arranged a funeral for it in which his friends marched in a procession, sang hymns, and listened to the composer recite a poem. No other written records of the bird appear in his surviving writings, but maybe the two had become collaborators.