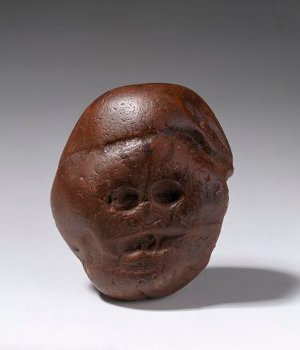

John Haberle’s 1889 trompe l’oeil masterpiece U.S.A. was such a faithful representation of a U.S. greenback that one could read the ironic government warning on the bill:

“Counterfeiting, or altering this note, or passing any counterfeit or alteration of it, or having in possession any false or counterfeit plate or impression of it, or any paper made in imitation of the paper on which it is printed, is punishable by $5000 fine or 15 years at hard labor or both.”

More than one viewer took it for an actual bill. When the painting was installed at the Art Institute of Chicago, the art critic of The Chicago Inter-Ocean objected: “There is a fraud hanging on the Institute walls. … It is that alleged still life by Haberle [in which] a $1 bill and the fragments of a $10 note have been pasted on canvas. … That the management of the Art Institute should hang this kind of ‘art’ even though it were genuine, is to be regretted, but to lend itself to such a fraud … is shameful.”

Haberle immediately took a train to Chicago and stood by while experts scrutinized the work through lenses, rubbed off paint, and declared it a genuine work of imitative art. The critic issued a public apology, acknowledging that others, including “Eastman Johnson, the dean of American figure and genre painters”, had also been taken in by Haberle’s works.