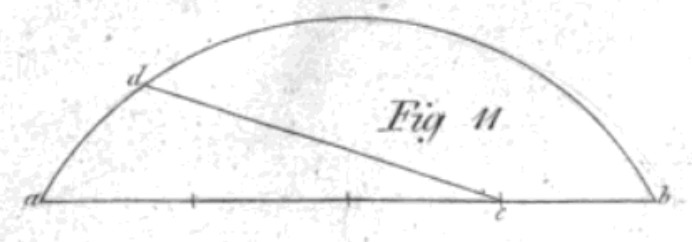

A popular mathematical puzzle asks: Suppose Earth were perfectly spherical and wrapped with a string at the equator. If we wanted to raise the string 1 meter off the ground, all around the world, how much longer would it need to be?

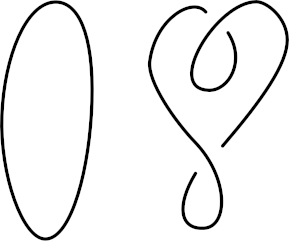

Surprisingly, the answer is only about 6.3 meters. A circle of radius r has a circumference of 2πr. We’re adding a meter to the radius, so the circumference increases by 2π meters.

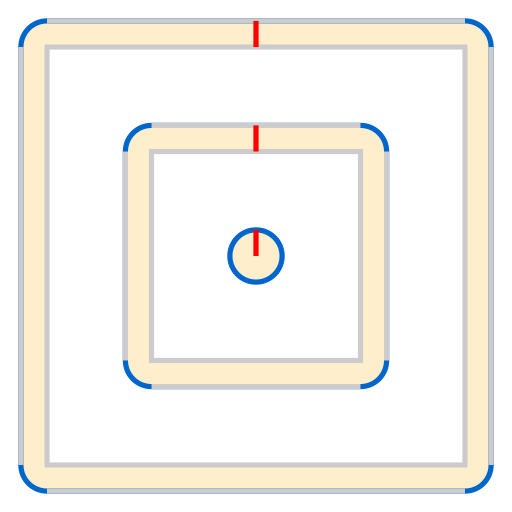

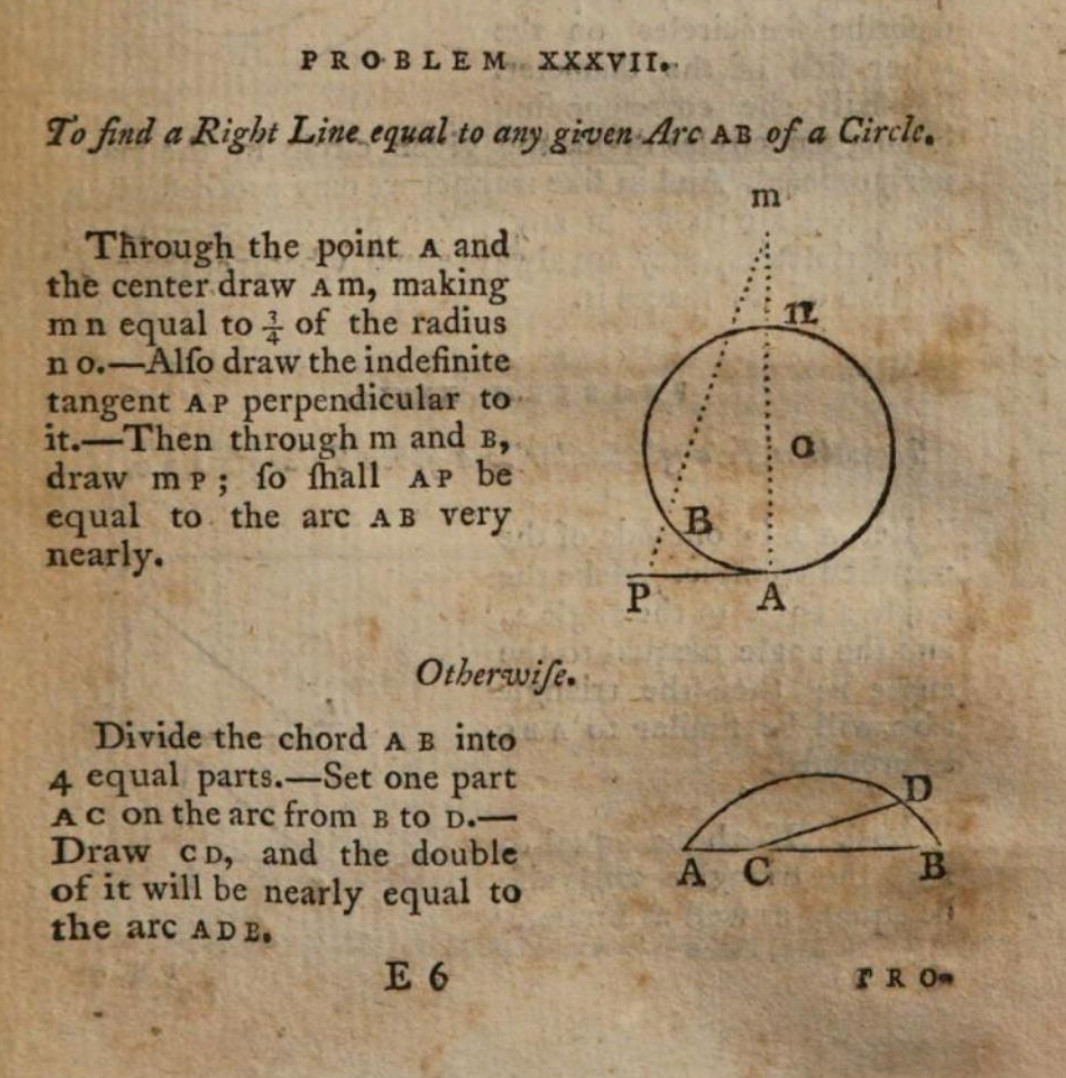

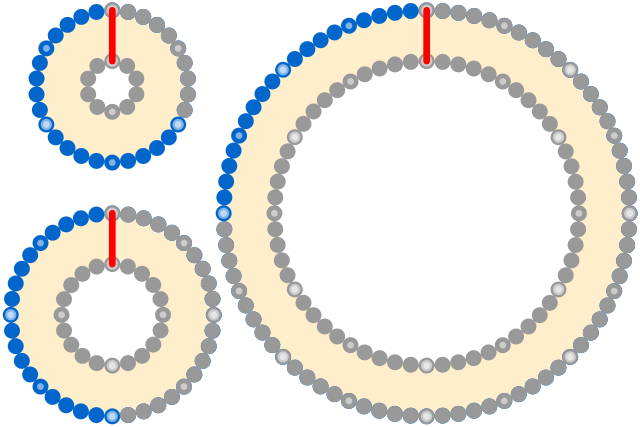

Even more remarkably, this remains true regardless of the size of the sphere. Above, the increase in the circumference (blue) remains the same for a sphere of any size — it’s determined entirely by the additional radius (red).

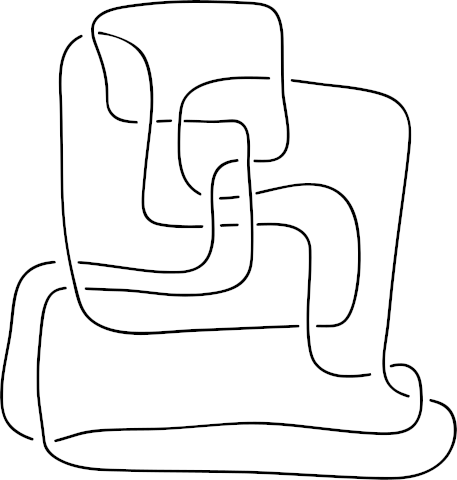

The shape need not even be a sphere! Below, when the string is raised one meter (red) outward from the perimeter of either square, the string’s total length increases only by the combined length of the four blue arcs, which together equal the circumference of a circle of radius 1, or 2π meters.