Raymond Queneau’s A Hundred Thousand Billion Poems consists of 10 sonnets with the same rhyming sounds, so that their 140 lines can be combined into 1014 different poems. Here’s an interactive version.

Milorad Pavić’s 1984 “lexicon novel” Dictionary of the Khazars consists of three miniature encyclopedias that cross-reference one another. Together they document, from varying perspectives, the causes of the disappearance of the Khazar empire in the eighth century. “Each reader will put together the book for himself, as in a game of dominoes or cards, and, as with a mirror, he will get out of this dictionary as much as he puts into it, for you … cannot get more out of the truth than what you put into it.”

Julio Cortázar’s 1963 “counter-novel” Hopscotch can be read in two ways: The reader can advance through the 56 chapters in conventional order or according to an alternate order laid out by the author, which incorporates 99 “expandable chapters” supplied at the end of the book. Thus the novel “consists of many books, but two books above all.”

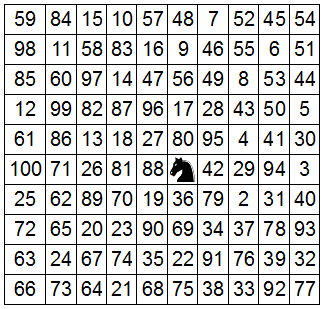

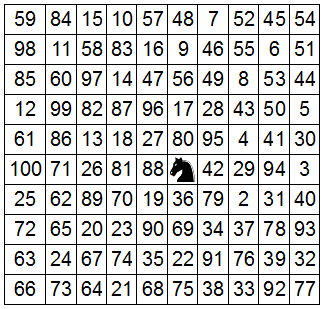

Georges Perec’s 1978 novel Life A User’s Manual concerns the lives of the inhabitants of a fictional Paris apartment house. Perec structured the novel by lifting off the building’s facade and mapping its rooms onto a 10×10 grid. He then placed an imaginary chess knight on a central square and worked out a tour that took the knight to every location in the building:

He used a similar technique to assign “elements” to each chapter: furniture, animals, clothes, jewels, music, books, toys, flowers, and more were salted into the building’s rooms according to the same rules. “With so much of its material predetermined,” wrote Perec biographer David Bellos, “the place of each chapter in the novel’s sequence, the place of each room described in the block of flats, and forty-two different things to say about every room — surely the book would just write itself.”

In fact Perec wrote it in 18 months. “Writing a novel is not like narrating something related directly to the real world,” he wrote. “It’s a matter of establishing a game between reader and writer.”