“In all the proof that has reached me, windrow has been spelled window. If, in the bound book, windrow still appears as window, then neither rain nor hail nor gloom of night nor fleets of riot squads will prevent me from assassinating the man who is responsible. If the coward hides behind my finding, I shall step into Scribner’s and merely shoot up the place Southern style.” — American author Gordon Dorrance (1890-1957), note to his publishers

“By the way, would you convey my compliments to the purist who reads your proofs and tell him or her that I write in a sort of broken-down patois which is something like the way a Swiss-waiter talks, and that when I split an infinitive, God damn it, I split it so it will remain split, and when I interrupt the velvety smoothness of my more or less literate syntax with a few sudden words of barroom vernacular, this is done with the eyes wide open and the mind relaxed and attentive. The method may not be perfect, but it is all I have.” — Raymond Chandler, to the editor of The Atlantic Monthly

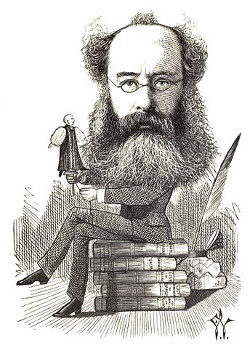

A publisher once took the liberty of editing an introduction that Mark Twain had contributed to a book on Joan of Arc. Twain returned a commentary on the edits. Some highlights:

- First line. What is the trouble with “at the”? And why “Trial?” Has some uninstructed person deceived you into the notion that there was but one, instead of half a dozen?

- Amongst. Wasn’t “among” good enough? …

- Second Paragraph. Now you have begun on my punctuation. Don’t you realize that you ought not to intrude your help in a delicate art like that, with your limitations? And do you think you have added just the right smear of polish to the closing clause of the sentence?

- Second Paragraph. How do you know it was his “own” sword? It could have been a borrowed one, I am cautious in matters of history, and you should not put statements in my mouth for which you cannot produce vouchers. Your other corrections are rubbish. …

- Fifth Paragraph. Thus far, I regard this as your masterpiece! You are really perfect in the great art of reducing simple and dignified speech to clumsy and vapid commonplace.

- Sixth Paragraph. You have a singularly fine and aristocratic disrespect for homely and unpretending English. Every time I use “go back” you get out your polisher and slick it up to “return.” “Return” is suited only to the drawing-room — it is ducal, and says itself with a simper and a smirk. …

- II. In Captivity. “Remainder.” It is curious and interesting to notice what an attraction a fussy, mincing, nickel-plated artificial word has for you. This is not well.

- Third Sentence. But she was held to ransom; it wasn’t a case of “should have been” and it wasn’t a case of “if it had been offered”; it was offered, and also accepted, as the second paragraph shows. You ought never to edit except when awake. …

- Third Paragraph. … “Break another lance” is a knightly and sumptuous phrase, and I honor it for its hoary age and for the faithful service it has done in the prize-composition of the schoolgirl, but I have ceased from employing it since I got my puberty, and must solemnly object to fathering it here. And besides, it makes me hint that I have broken one of those things before, in honor of the Maid, an intimation not justified by the facts. I did not break any lances or other furniture, I only wrote a book about her.

The full list is in his autobiography. “It cost me something to restrain myself and say these smooth and half-flattering things to this immeasurable idiot,” Twain wrote, “but I did it and have never regretted it. For it is higher and nobler to be kind to even a shad like him than just. If we should deal out justice only, in this world, who would escape?”