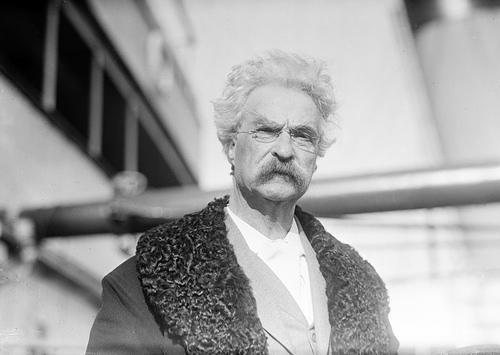

“The German long word is not a legitimate construction, but an ignoble artificiality, a sham,” wrote Mark Twain. “Nothing can be gained, no valuable amount of space saved, by jumbling the following words together on a visiting card: ‘Mrs. Smith, widow of the late Commander-in-chief of the Police Department,’ yet a German widow can persuade herself to do it, without much trouble: ‘Mrs.-late-commander-in-chief-of-the-police-department’s-widow-Smith.'” He gives this anecdote in his autobiography:

A Dresden paper, the Weidmann, which thinks that there are kangaroos (Beutelratte) in South Africa, says the Hottentots (Hottentoten) put them in cages (kotter) provided with covers (lattengitter) to protect them from the rain. The cages are therefore called lattengitterwetterkotter, and the imprisoned kangaroo lattengitterwetterkotterbeutelratte. One day an assassin (attentäter) was arrested who had killed a Hottentot woman (Hottentotenmutter), the mother of two stupid and stuttering children in Strättertrotel. This woman, in the German language is entitled Hottentotenstrottertrottelmutter, and her assassin takes the name Hottentotenstrottermutterattentäter. The murderer was confined in a kangaroo’s cage — Beutelrattenlattengitterwetterkotter — whence a few days later he escaped, but fortunately he was recaptured by a Hottentot, who presented himself at the mayor’s office with beaming face. ‘I have captured the Beutelratte,’ said he. ‘Which one?’ said the mayor; ‘we have several.’ ‘The Attentäterlattengitterwetterkotterbeutelratte.’ ‘Which attentäter are you talking about?’ ‘About the Hottentotenstrottertrottelmutterattentäter.’ ‘Then why don’t you say at once the Hottentotenstrottelmutterattentäterlattengitterwetterkotterbeutelratte?’

He calls the long word “a lazy device of the vulgar and a crime against the language.”