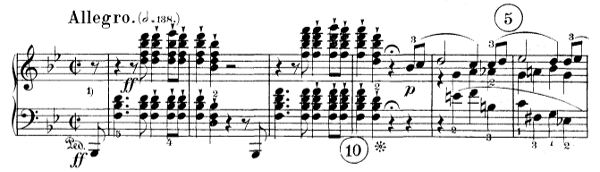

The first movement of Beethoven’s piano sonata no. 29, the Hammerklavier, bears a puzzlingly fast tempo marking, half-note=138. Most pianists play it considerably more slowly, judging that the indicated tempo would test the limits of the player’s technique and the listeners’ comprehension.

Well, most listeners. In Fred Hoyle’s 1957 science fiction novel The Black Cloud, an intelligent cloud of gas enters the solar system and establishes communication with the earth. It demonstrates a superhumanly subtle understanding of any information that’s transmitted to it. As scientists are uploading a sampling of Earth music, a lady remarks, “The first movement of the B Flat Sonata bears a metronome marking requiring a quite fantastic pace, far faster than any normal pianist can achieve, certainly faster than I can manage.”

The cloud considers the sonata and says, “Very interesting. Please repeat the first part at a speed increased by thirty percent.”

When this is done, it says, “Better. Very good. I intend to think this over.”