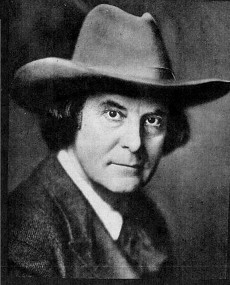

Jack London died in 1916, but he turned up, gamely, in 1920 when psychic Margaret More Oliver tried to reach him through automatic writing. “I am at last attuned to life,” he wrote. “There is no discord — no conflict — the clash of mind and will with heart and impulse of soul has ended.”

She proposed that he write a story through her, and after many false starts they succeeded. “I am getting it over!” he wrote. “I am jubilant! Oh, God! it’s good to be able to do it. My pen is coming back to earth and I shall do wonders yet.”

She sent the manuscript to London’s widow, Charmian, proposing to publish it as “Death’s Sting, by Jack London, Deceased.” But Charmian refused: “If I allowed a book to come out under such ‘authorship,’ immediately every faker in the land — and they are legion — would have perfect right to do the same … the selling value of bona fide work of Jack London’s would be more or less injured, and too much depends on this.”

Oliver pressed her, but Charmian was adamant: “If I should ever be convinced, beyond the flutter of a doubt, I’d eat cyanide of potassium so quickly that I’d be on the Other Side, groping around for Jack, before I had time to think about it!”

The text of Death’s Sting seems to have been lost, but evidently it wasn’t very good — Charmian’s aunt, Netta Payne, wrote, “It has no touch of literary merit, no hint of power or idealistic beauty. It is a tedious detail of sordid facts without the least alleviation of literary artistry.” London’s spirit finally agreed: “I tried to speak with my old tongue, but my old tongue is silenced.”

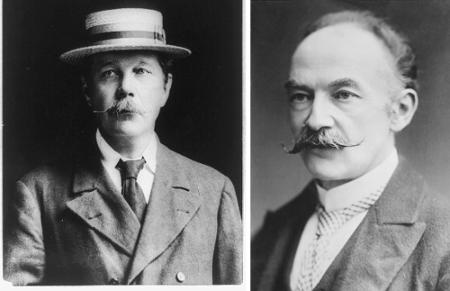

One person who wasn’t surprised at any of this was Arthur Conan Doyle, who had written to Charmian a year after London’s death to suggest that “a strong soul dying prematurely with many earth interests in its thoughts, would be very likely to come back.”

“Mrs. London received my intrusion with courtesy,” Doyle wrote, “but I am not aware that any practical steps were taken toward this end. They seem now to have come from the other side.”

(Edward Biron Payne, The Soul of Jack London, 1927.)