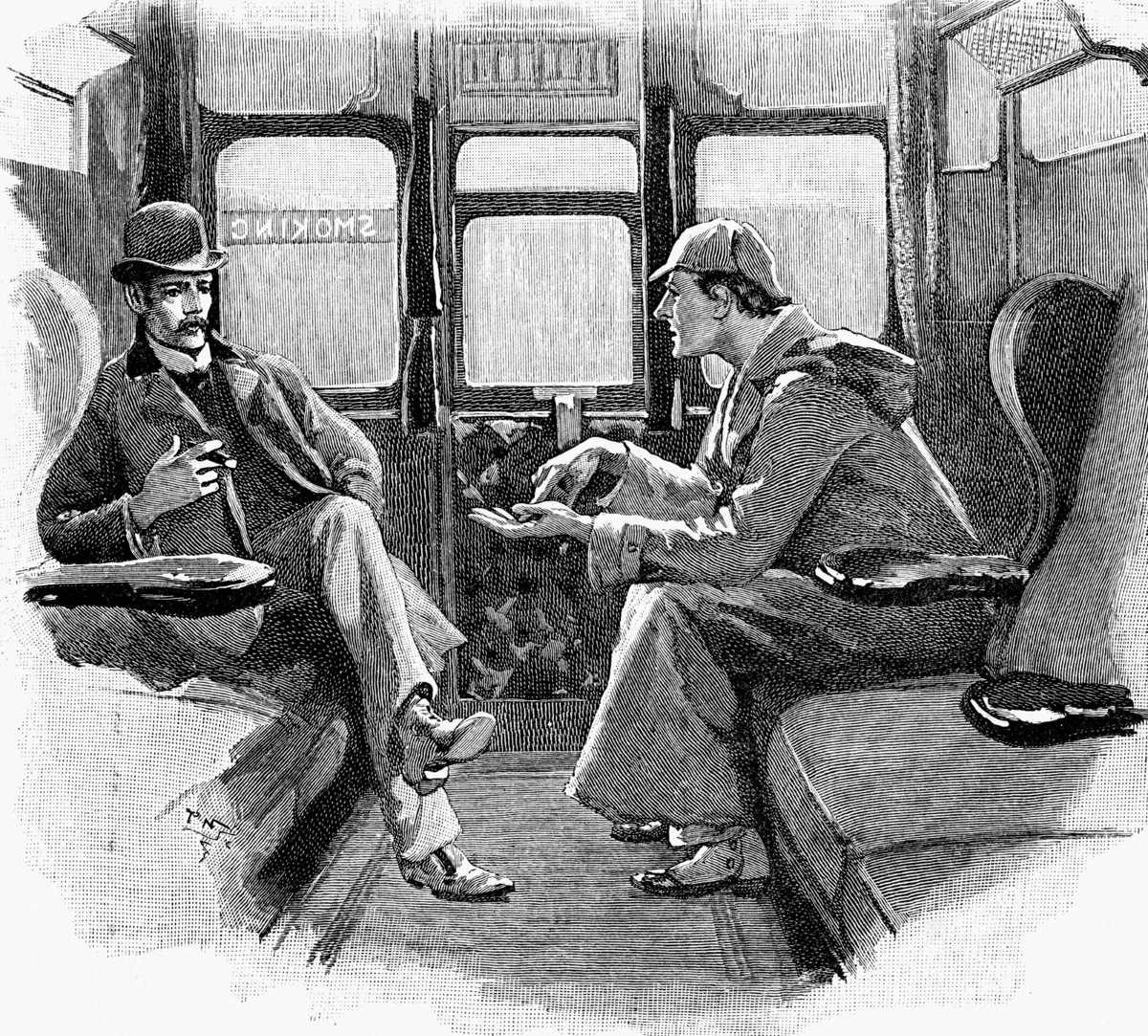

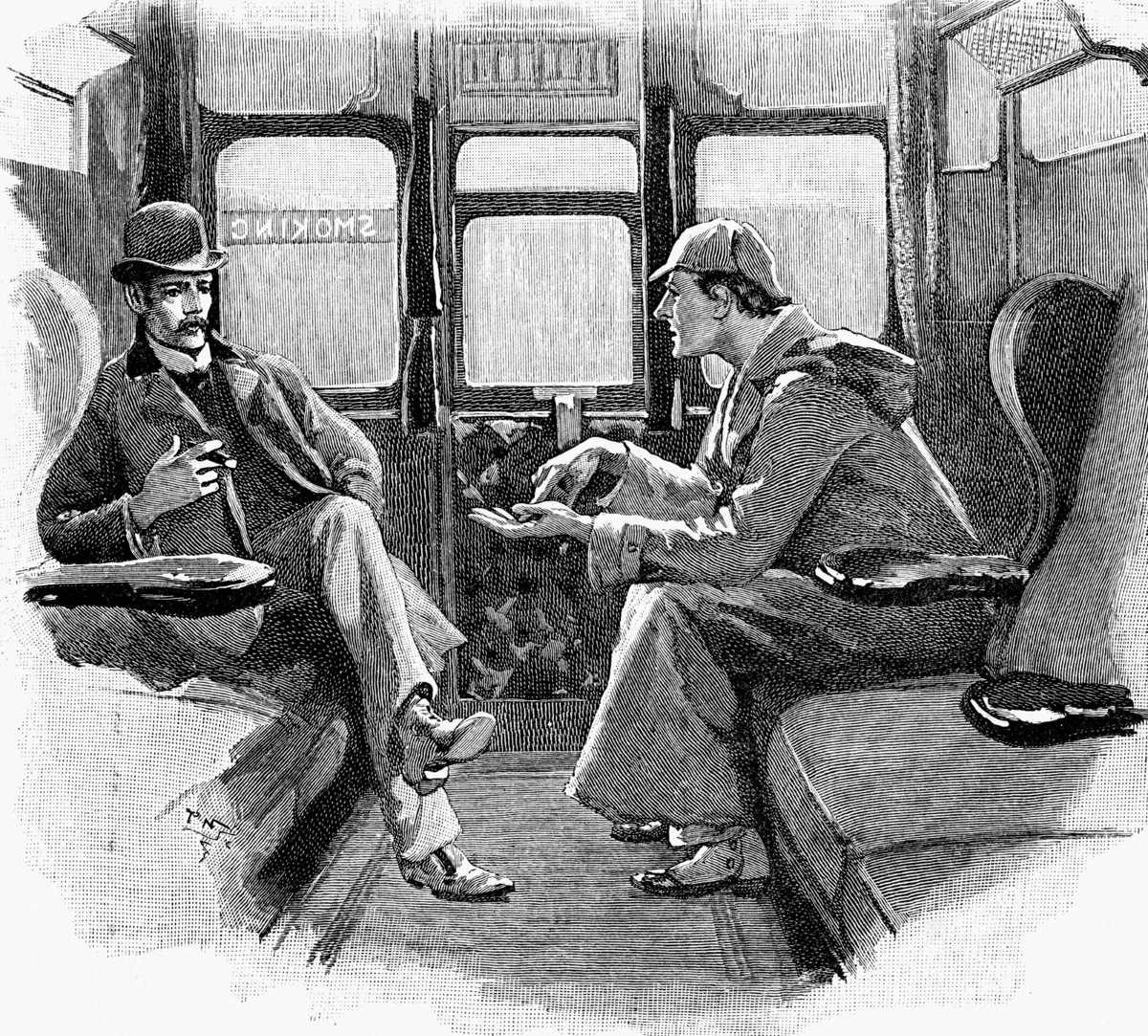

At the start of the 1892 story “Silver Blaze,” Sherlock Holmes and Watson set out on a train journey from Paddington to Swindon in a first-class train carriage.

“We are going very well,” says Holmes, looking out the window and glancing at his watch. “Our rate at present is fifty-three and a half miles an hour.”

“I have not observed the quarter-mile posts,” says Watson.

“Nor have I,” replies Holmes. “But the telegraph posts upon this line are sixty yards apart, and the calculation is a simple one.”

Is it? The speed itself is plausible — trains were allowed 87 minutes to travel the route, giving an average speed of 53.25 mph, and so the top running speed would have been higher than this. But A.D. Galbraith complained that the detective’s casual statement is “completely inconsistent with Holmes’ character.” Using the second hand of his watch, he’d had to mark the passage of two successive telegraph posts, probably a mile or more apart, and count the posts between them; an error of more than one second would produce an error of almost half a mile an hour. So Holmes’ scrupulous dedication to accuracy should have led him to say “between 53 and 54 miles an hour” or even “between 52 and 55.”

Guy Warrack, in Sherlock Holmes and Music, agreed: It would have been impossible to time the passage of the telegraph poles to the necessary precision using a pocket watch. But S.C. Roberts, in a review of the book, disagreed:

Mr. Warrack, if we may so express it, is making telegraph-poles out of fountain-pens. What happened, surely, was something like this: About half a minute before he addresssed Watson, Holmes had looked at the second hand of his watch and then counted fifteen telegraph poles (he had, of course, seen the quarter-mile posts, but had not observed them, since they were not to be the basis of his calculation). This would give him a distance of nine hundred yards, a fraction over half-a-mile. If a second glance at his watch had shown him that thirty seconds had passed, he would have known at once that the train was traveling at a good sixty miles an hour. Actually he noted that the train had taken approximately thirty-four seconds to cover the nine hundred yards; or, in other words, it was rather more than ten per cent (i.e., 6 1/2 from sixty). The calculation, as he said, was a simple one; what made it simple was his knowlege, which of course Watson did not share, that the telegraph poles were sixty yards apart.

In fact George W. Welch offered two different formulas that Holmes might have used:

First Method:–Allow two seconds for every yard, and add another second for every 22 yards of the known interval. Then the number of objects passed in this time is the speed in miles an hour. Proof:–Let x = the speed in miles per hour, y = the interval between adjacent objects. 1 m.p.h. = 1,760 yards in 3,600 seconds = 1 yard in 3,600/1,760 = 45/22 or 2.1/22 secs. = y yards in 2.1/22 y seconds x m.p.h. = xy yards in 2.1/22y seconds. Example:–Telegraph poles are set 60 yards apart. 60 × 2 = 120; 60 ÷ 22 = 3 (approx.); 120 + 3 = 123. Then, if after 123 seconds the observer is half-way between the 53rd and 54th poles, the speed is 53 1/2 miles an hour.

Second Method:–When time or space will not permit the first method to be used, allow one second for every yard of the known interval, and multiply by 2.1/22 the number of objects passed in this time. The product is the speed in miles an hour. Example:–Telegraph poles are set 60 yards apart. After 60 seconds the observer is about 10 yards beyond the 26th pole. 26.1/6 × 2 = 52.1/3; 26.1/6 divided by 22 = 1.1/6 (approx.); 52.1/3 = 1.1/6 = 53 1/2. Therefore the speed is 53 1/2 miles an hour. The advantage of the first method is that the time to be used can be worked out in advance, leaving the observer nothing to do but count the objects against the second hand of his watch.

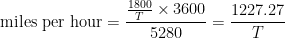

Julian Wolff suggested examining the problem “in the light of pure reason.” The speed in feet per second is found by determining the number of seconds required to travel a known number of feet. Holmes says that the posts are 60 yards apart, so 10 intervals between poles is 1800 feet, and the speed in covering this distance is 1800/T feet per second. Multiply that by 3600 gives feet per hour, and dividing the answer by 5280 gives the speed in miles per hour. So:

So to get the train’s speed in miles per hour we just have to divide 1227.27 by the number of seconds required to travel 1800 feet. And “1227 is close enough for all ordinary purposes, such as puzzling Watson, for instance.”

(From William S. Baring-Gould, ed., The Annotated Sherlock Holmes, 1967.)