“I’m sorry, Mr Kipling, but you just don’t know how to use the English language.” — San Francisco Examiner, rejecting a submission by Rudyard Kipling, 1889

Literature

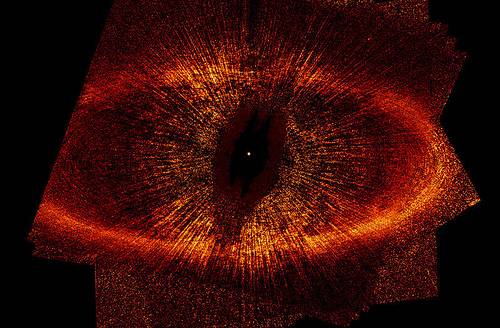

The Eye of Sauron

The Eye was rimmed with fire, but was itself glazed, yellow as a cat’s, watchful and intent, and the black slit of its pupil opened on a pit, a window into nothing.

That’s a quote from The Fellowship of the Ring, but this image is actually a star. Fomalhaut, 25 light-years away, is one of the brightest stars in the night sky.

Draw your own conclusions.

Stirred, Not Shaken

Beginning work on a new novel in 1953, Ian Fleming found himself stumped for a name for his hero, a British Secret Service agent. His eye strayed across the bookshelves of his Jamaican estate, and he found “just what I needed.”

It was Birds of the West Indies, by James Bond.

Writer’s Block

A young man once accosted James Joyce and asked, “May I kiss the hand that wrote Ulysses?”

Joyce replied, “No, it did a lot of other things, too.”

Unquote

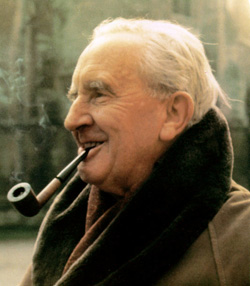

“Oh no! Not another fucking elf!” — Oxford English professor Hugo Dyson, interrupting J.R.R. Tolkien during an early reading from The Lord of the Rings

Oh Well

In the early 1960s, a computer analysis showed that six different authors had written the Epistles of St. Paul.

That would be big news, but it also showed that James Joyce’s Ulysses had been written by five people — none of whom had composed A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man.

A Dead Language Revived

Jonathan Swift liked to compose “Latin puns” — stanzas of nonsense Latin that would render English when spoken:

Mollis abuti,

Has an acuti,

No lasso finis,

Molli divinis.

Omi de armis tres,

Cantu disco ver

Meas alo ver?

Read that aloud and you’ll hear:

Moll is a beauty,

Has an acute eye,

No lass so fine is,

Molly divine is.

O my dear mistress,

I’m in a distress,

Can’t you discover

Me as a lover?

In a later letter, Swift wrote:

I ritu a verse o na molli o mi ne,

Asta lassa me pole, a l(ae)dis o fine;

I ne ver neu a niso ne at in mi ni is;

A manat a glans ora sito fer diis.

De armo lis abuti hos face an hos nos is

As fer a sal illi, as reddas aro sis;

Ae is o mi molli is almi de lite;

Illo verbi de, an illo verbi nite.

I writ you a verse on a Molly o’ mine,

As tall as a May-pole, a lady so fine;

I never knew any so neat in mine eyes;

A man, at a glance or a sight of her, dies

Dear Molly’s a beauty, whose face and whose nose is

As fair as a lily, as red as a rose is;

A kiss o’ my Molly is all my delight;

I love her by day, and I love her by night.

See also this verse.

Warm Words

It is said that, when Charles Dudley Warner was the editor of the ‘Hartford Press,’ back in the ‘sixties,’ arousing the patriotism of the State with his vigorous appeals, one of the type-setters came in from the composing-room, and, planting himself before the editor, said: ‘Well, Mr. Warner, I’ve decided to enlist in the army.’ With mingled sensations of pride and responsibility, Mr. Warner replied encouragingly that he was glad to see the man felt the call of duty. ‘Oh, it isn’t that,’ said the truthful compositor, ‘but I’d rather be shot than try to set any more of your damned copy.’

— John Wilson, “The Importance of the Proof-Reader,” 1901

Size Doesn’t Matter

RMS Queen Mary was one of the world’s largest ocean liners in December 1942, but that didn’t impress Mother Nature. As the ship steamed off the coast of Scotland during a gale, an enormous freak wave struck her broadside and sent her listing fully 52 degrees. The wave may have been 28 meters high; it smashed windows on the bridge 90 feet above the waterline. Later investigations estimated that 5 more inches of list would have turned her over.

The incident inspired Paul Gallico to write The Poseidon Adventure.

Dear My Frankly

Margaret Mitchell composed Gone With the Wind while nursing a broken ankle.

She wrote the last chapter first and the first chapter last.