In 1929, detective novelist Arthur Upfield wanted to devise the perfect murder, so he started a discussion among his friends in Western Australia. He was pleased with their solution — until local workers began disappearing, as if the book were coming true. In this week’s episode of the Futility Closet podcast we’ll describe the Murchison murders, a disturbing case of life imitating art.

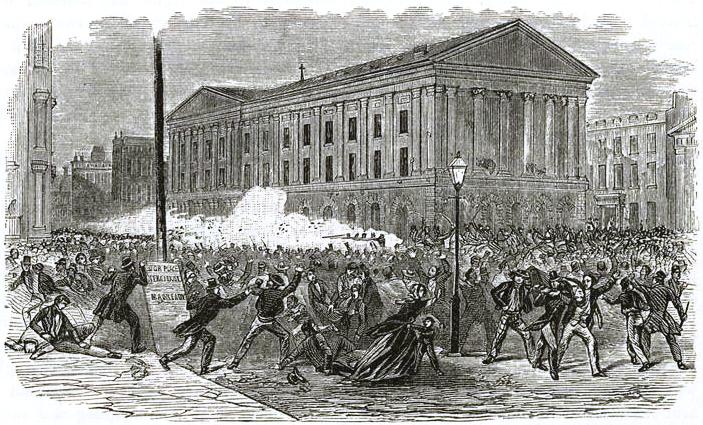

We’ll also incite a revolution and puzzle over a perplexing purchase.