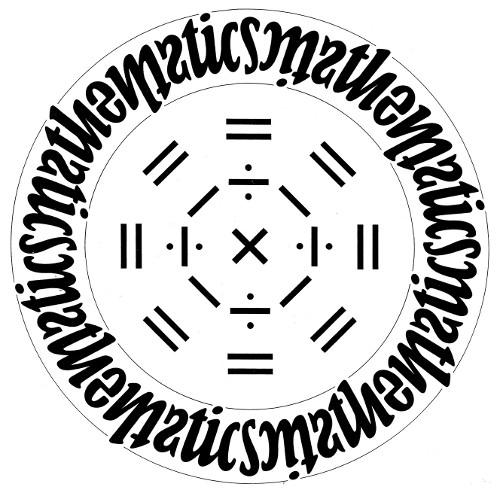

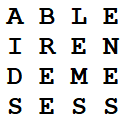

REMEDIABLENESSES, written in a spiral, produces a 4 × 4 word square all of whose entries appear in the Oxford English Dictionary.

IREN is a variant of iron, a DEME is an arbiter or ruler, a SESS is an assessment, the BREE is the eyelid, LEMS are lunar excursion modules, and ENES is an archaic form of once.

(Jeff Grant, “Some of My Favorite Squares,” Word Ways 40:2 [May 2007], 96-102.)