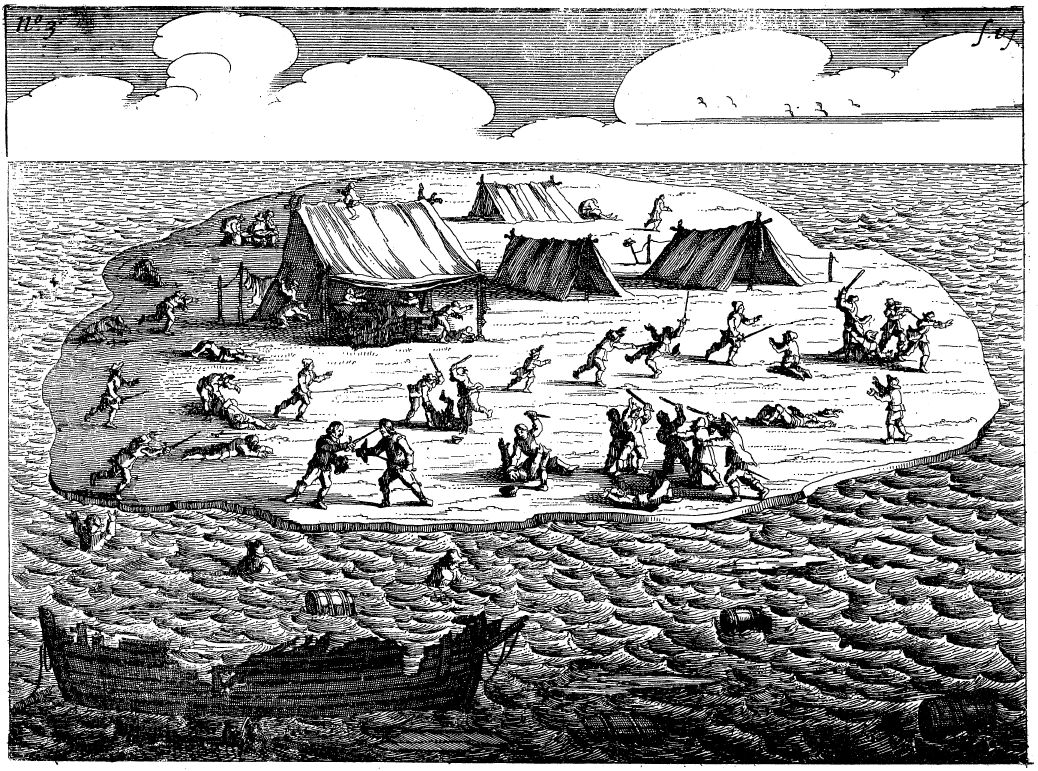

Each Ascension Day between 1311 and 1798, the doge of Venice was rowed into the Adriatic aboard a palatial barge to perform the “Marriage of the Sea,” a ceremony that symbolically wedded Venice to the sea. The ship, known as the Bucentaur, led a solemn procession of boats out of the city, where the doge dropped a consecrated ring into the water with the words Desponsamus te, mare (“We wed thee, sea”) to indicate that the city and the sea were indissolubly one.

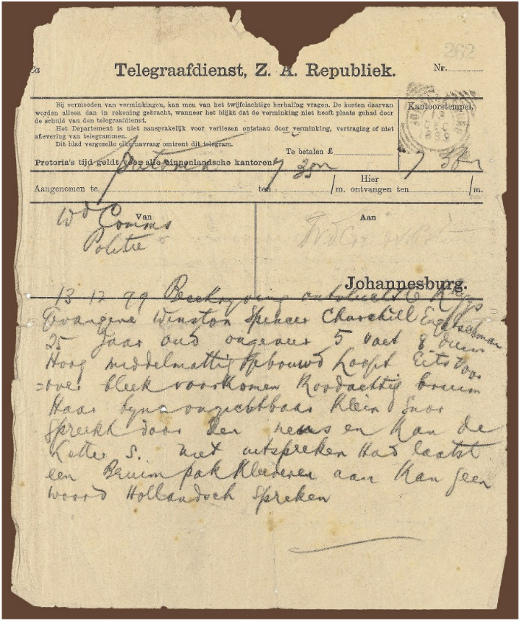

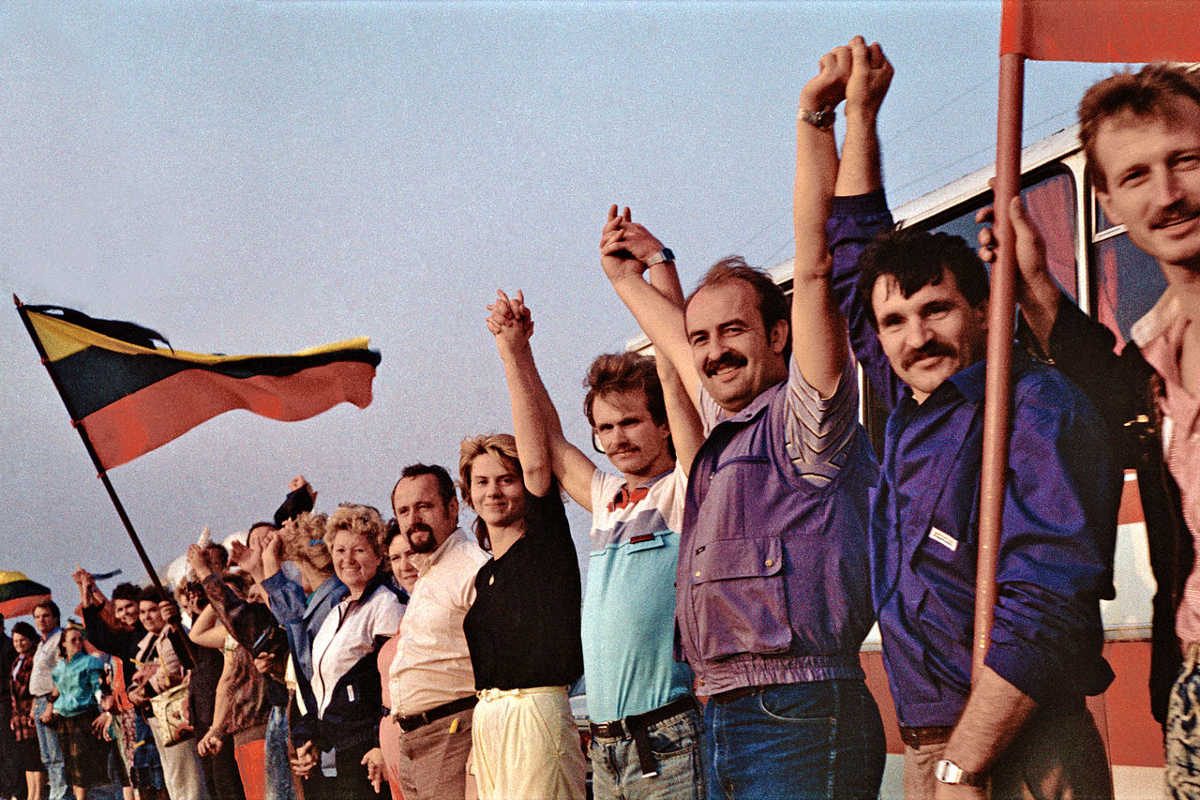

After the Treaty of Versailles, Polish general Jozef Haller marked his country’s renewed access to the Baltic Sea by throwing a ring into the water with the words “In the name of the Holy Republic of Poland, I, General Jozef Haller, am taking control of this ancient Slavic Baltic Sea shore”:

His act was repeated in 1945 in several ceremonies by members of the First Polish Army, who threw rings, dipped flags, and swore an oath pledging their nation’s devotion to the Baltic. The text of the oath was later printed in the Polish Army newspaper Zwyciezymy: “I swear to you, Polish Sea, that I, a soldier of the Homeland, faithful son of the Polish nation, will not abandon you. I swear to you that I will always follow this road, the road which has been paved by the State National Council, the road which has led me to the sea. I will guard you, I will not hesitate to shed my blood for the Fatherland, neither will I hesitate to give my life so that you do not return to Germany. You will remain Polish forever.”