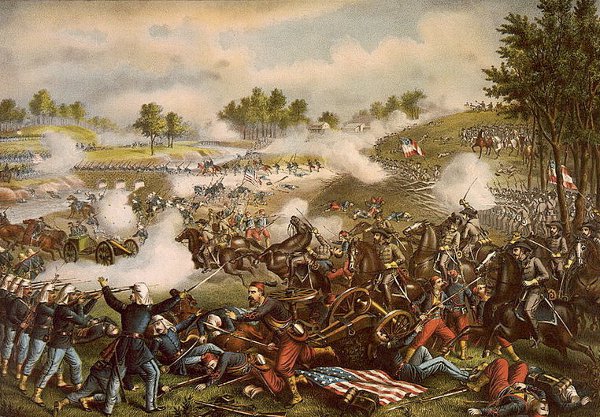

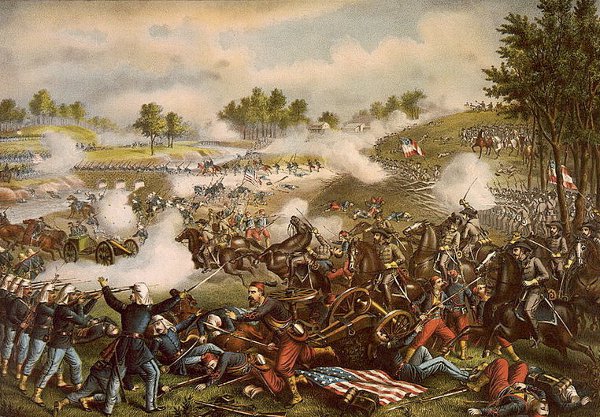

After the First Battle of Manassas, a reporter for the Richmond Dispatch discovered a Confederate soldier tending to a wounded Union infantryman.

“Yes, sir, he is my brother Henry,” he said. “The same mother bore us, the same mother nursed us. We met for the first time in four years. I belong to the Washington Artillery, from New Orleans–he to the First Minnesota Infantry. By the merest chance I learned he was here wounded, and sought him out to nurse and attend to him.”

“Thus they met,” the reporter wrote, “one from the far North, the other from the extreme South–on a bloody field in Virginia, in a miserable stable, far away from their mother, home and friends, both wounded–the infantry man by a musket ball in the right shoulder, the artillery man by the wheel of a caisson over his left hand. Their names are Frederick Hubbard, Washington Artillery, and Henry Hubbard, First Minnesota Infantry.”