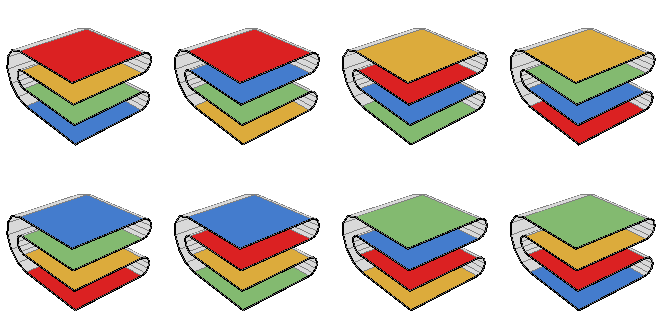

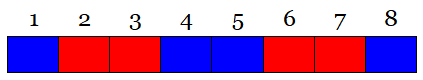

Number eight cells:

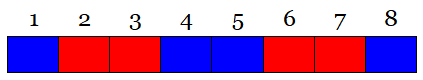

Now suppose we want to color each cell red or blue such that no three cells are in arithmetic progression — for example, we don’t want cells 1, 2, and 3 to be the same color, or 4, 6, and 8. With eight cells it’s possible to accomplish this:

But if we want to add a ninth cell we can’t avoid an arithmetic progression: If the ninth cell is blue then cells 1, 5, and 9 are evenly spaced, and if it’s red then cells 3, 6, and 9 are. Dutch mathematician B.L. van der Waerden found that there’s always such a limit: For any given positive integers r and k, there’s some number N such that if the integers {1, 2, …, N} are colored, each with one of r different colors, then there will be at least k integers in arithmetic progression whose elements are of the same color. Determining what this limit is (in this example it’s 9) is an open problem.

(Bonus: Alexej Kanel-Belov found this pretty theorem concerning divisibility of integer sums within an infinite grid — Martin J. Erickson, in Beautiful Mathematics, calls it a two-dimensional version of van der Waerden’s theorem.)