Justice Arthur Gilbert of the California Court of Appeal felt that legal motions might be more interesting if they were written in the styles of famous authors. He proposed these motions for continuance:

Ernest Hemingway:

It was busy and there was commotion. I looked out the window where the wind touched the top of the trees and far below, the street, white from the sunlight, and the cars inching forward, but I could feel up here that it would not be good, but there was nothing one could do. Pilar, my secretary, looked at me and her eyes told me that this was as bad as when the bulls are running toward you and there is nowhere to climb and you know you will be trampled, but you know that until they do you can live a good life, a short, happy life. And when I asked her for the file and she said, “What file, Ingles?” I knew that the bulls were loose and there was nowhere to go; there was no yesterday, no tomorrow, but that was then and now is here, Your Honor. There was a time when it was good, but now it is a time when it is bad and you can make it good again, and if you can’t, it’s a rotten shame.

T.S. Eliot:

Thirty days to answer.

It’s the cruelest month.

Dead, dying decay, an apt description

For my brain, withered, not resplendent now,

A supplicant, having been etherized upon a table

During the time to answer.

I ask for relief,

Not with a bang, but a whimper.

James Joyce:

HelpmeohGod Time is creptupandI saidyesohheyesyesyesyesI need relief nowfromignominious default default fault-d de fault is mine ohhelptheteatiscaughtintheproceduralwringer. Relief.

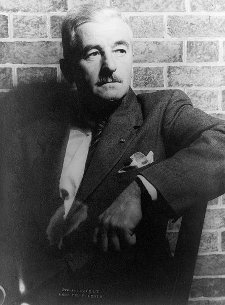

William Faulkner:

Benji had taken the file and went along the fence with it and lost it through the spaces in the fence where the flowers were curling. That’s what they said. I started to cry. Caddy, who smelled like trees, and Quentin, who just smelled, came to find the file, but I didn’t holler ’til mother shouted at Dilsey for bringing me cheap store cake. Dilsey took me up to bed. Quentin told Caddy he had to answer. He had to find the file. Caddy did not know that Benji had taken the file, and Benji could not know that he had taken the file, because this motion is written from Benji’s point of view, and his IQ is 17.