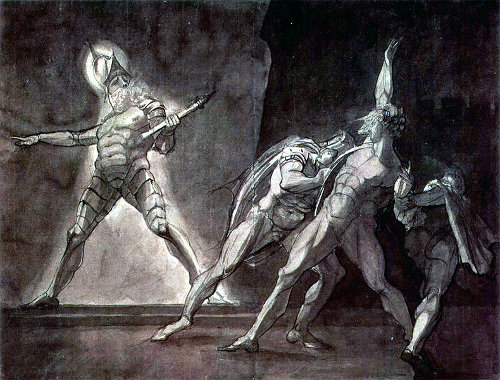

In 1889 Fredericka Beardsley Gilchrist advanced a theory that the entire meaning of Hamlet has been confused because of a typographical error. In Act I, Scene V, the ghost reveals to Hamlet his mother’s adultery and his father’s murder. Hamlet responds:

O all you host of heaven! O earth! what else?

And shall I couple hell? O fie!

Gilchrist maintains that the second line should read:

And shall I couple? Hell! O fie!

In other words, “And after this shall I also marry? No!” He gives up his love for Ophelia, and the rest of the play is the story of “an unhappy lover.”

For Gilchrist this is “the one key that unlocks every difficulty in the play”: “For nearly three hundred years it has been possible to misunderstand, not special passages only, but the fundamental intention of the play; during that time no satisfactory explanation of all its obscurities has been advanced. I believe this theory explains them; and this belief, based on careful study and comparison, ought to excuse the seeming vanity and presumption of the preceding statement.”

Decide for yourself — her book is here.