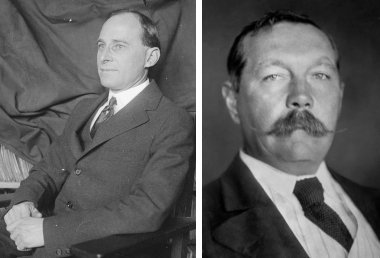

In 1915, critic Arthur Guiterman addressed a poem “To Sir Arthur Conan Doyle”:

Holmes is your hero of drama and serial;

All of us know where you dug the material

Whence he was moulded — ’tis almost a platitude;

Yet your detective, in shameless ingratitude —

Sherlock your sleuthhound with motives ulterior

Sneers at Poe’s “Dupin” as “very inferior!”

Labels Gaboriau’s clever “Lecoq”, indeed,

Merely “a bungler”, a creature to mock, indeed!

This, when your plots and your methods in story owe

More than a trifle to Poe and Gaboriau,

Sets all the Muses of Helicon sorrowing.

Borrow, Sir Knight, but be decent in borrowing!

Conan Doyle responded with “To an Undiscerning Critic”:

Sure there are times when one cries with acidity,

“Where are the limits of human stupidity?”

Here is a critic who says as a platitude

That I am guilty because “in ingratitude

Sherlock, the sleuth-hound, with motives ulterior,

Sneers at Poe’s Dupin as very ‘inferior’.”

Have you not learned, my esteemed commentator,

That the created is not the creator?

As the creator I’ve praised to satiety

Poe’s Monsieur Dupin, his skill and variety,

And have admitted that in my detective work

I owe to my model a deal of selective work.

But is it not on the verge of inanity

To put down to me my creation’s crude vanity?

He, the created, would scoff and would sneer,

Where I, the creator, would bow and revere.

So please grip this fact with your cerebral tentacle:

The doll and its maker are never identical.