In 1916, after extensive study, French writer Georges Polti announced that all the stories in classical and modern literature could be reduced to 36 essential situations:

- Supplication. The Persecutor accuses the Suppliant of wrongdoing, and the Power makes a judgment against the Suppliant.

- Deliverance. The Unfortunate has caused a conflict, and the Threatener is to carry out justice, but the Rescuer saves the Unfortunate.

- Crime pursued by vengeance. The Criminal commits a crime that will not see justice, so the Avenger seeks justice by punishing the Criminal.

- Vengeance taken for kin upon kin. Two entities, the Guilty and the Avenging Kinsmen, are put into conflict over wrongdoing to the Victim, who is allied to both.

- Pursuit. The Fugitive flees Punishment for a misunderstood conflict.

- Disaster. The Power falls from their place after being defeated by the Victorious Enemy or being informed of such a defeat by the Messenger.

- Falling prey to cruelty/misfortune. The Unfortunate suffers from Misfortune and/or at the hands of the Master.

- Revolt. The Tyrant, a cruel power, is plotted against by the Conspirator.

- Daring enterprise. The Bold Leader takes the Object from the Adversary by overpowering the Adversary.

- Abduction. The Abductor takes the Abducted from the Guardian.

- The enigma. The Interrogator poses a Problem to the Seeker and gives a Seeker better ability to reach the Seeker’s goals.

- Obtaining. The Solicitor is at odds with the Adversary who refuses to give the Solicitor what they Object in the possession of the Adversary, or an Arbitrator decides who gets the Object desired by Opposing Parties (the Solicitor and the Adversary).

- Enmity of kin. The Malevolent Kinsman and the Hated or a second Malevolent Kinsman conspire together.

- Rivalry of kin. The Object of Rivalry chooses the Preferred Kinsman over the Rejected Kinsman.

- Murderous adultery. Two Adulterers conspire to kill the Betrayed Spouse.

- Madness. The Madman goes insane and wrongs the Victim.

- Fatal imprudence. The Imprudent, by neglect or ignorance, loses the Object Lost or wrongs the Victim.

- Involuntary crimes of love. The Revealer betrays the trust of either the Lover or the Beloved.

- Slaying of kin unrecognized. The Slayer kills the Unrecognized Victim.

- Self-sacrifice for an ideal. The Hero sacrifices the Person or Thing for their Ideal, which is then taken by the Creditor.

- Self-sacrifice for kin. The Hero sacrifices a Person or Thing for their Kinsman, which is then taken by the Creditor.

- All sacrificed for passion. A Lover sacrifices a Person or Thing for the Object of their Passion, which is then lost forever.

- Necessity of sacrificing loved ones. The Hero wrongs the Beloved Victim because of the Necessity for their Sacrifice.

- Rivalry of superior vs. inferior. A Superior Rival bests an Inferior Rival and wins the Object of Rivalry.

- Adultery. Two Adulterers conspire against the Deceived Spouse.

- Crimes of love. A Lover and the Beloved enter a conflict.

- Discovery of the dishonour of a loved one. The Discoverer discovers the wrongdoing committed by the Guilty One.

- Obstacles to love. Two Lovers face an Obstacle together.

- An enemy loved. The allied Lover and Hater have diametrically opposed attitudes towards the Beloved Enemy.

- Ambition. The Ambitious Person seeks the Thing Coveted and is opposed by the Adversary.

- Conflict with a god. The Mortal and the Immortal enter a conflict.

- Mistaken jealousy. The Jealous One falls victim to the Cause or the Author of the Mistake and becomes jealous of the Object and becomes conflicted with the Supposed Accomplice.

- Erroneous judgment. The Mistaken One falls victim to the Cause of the Author of the Mistake and passes judgment against the Victim of the Mistake when it should be passed against the Guilty One instead.

- Remorse. The Culprit wrongs the Victim or commits the Sin, and is at odds with the Interrogator who seeks to understand the situation.

- Recovery of a lost one. The Seeker finds the One Found.

- Loss of loved ones. The killing of the Kinsman Slain by the Executioner is witnessed by the Kinsman Spectator.

For example, the Sherlock Holmes stories are an example of situation 3; Madame Bovary of situation 25; Romeo and Juliet of situation 29; and Crime and Punishment of situation 34. (The full text is here.) Correspondingly, he claimed, in life there are only 36 emotions, whose “unceasing ebb and flow … fills human history like the tides of the sea.”

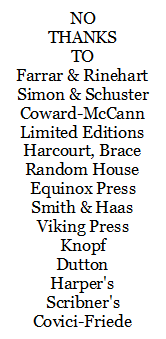

Though he found that 36 categories were enough “to distribute fitly among them the innumerable dramas awaiting classification,” Polti felt that his system shouldn’t inhibit the creativity of future writers. “Any writer may have here a starting-point for observation and creation, outside the world of paper and print, a starting-point personal to himself.”