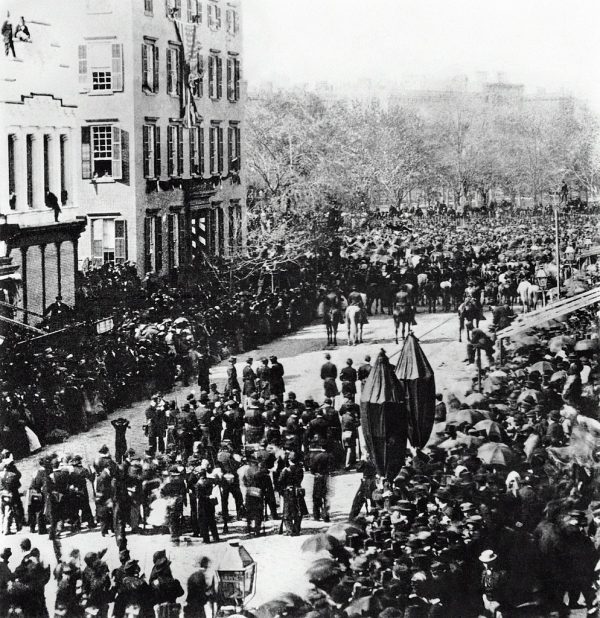

In the 1940s, journalist Stefan Lorant was researching a book on Abraham Lincoln when he came upon a photograph of the president’s funeral procession as it moved down Broadway in New York City. The image was dated April 25, 1865.

As Lorant tried to identify the location, he found that the shuttered house on the left belonged to Cornelius van Schaack Roosevelt, the grandfather of future president Teddy Roosevelt and his brother Elliott. Teddy would have been 6 years old at the time of the procession. And visible in a second-story window are the heads of two boys.

As it happened, Lorant had an opportunity to ask Roosevelt’s widow Edith about the image. “Yes, I think that is my husband, and next to him his brother,” she said. “That horrible man! I was a little girl then and my governess took me to Grandfather Roosevelt’s house on Broadway so I could watch the funeral procession. But as I looked down from the window and saw all the black drapings I became frightened and started to cry. Theodore and Elliott were both there. They didn’t like my crying. They took me and locked me in a back room. I never did see Lincoln’s funeral.”