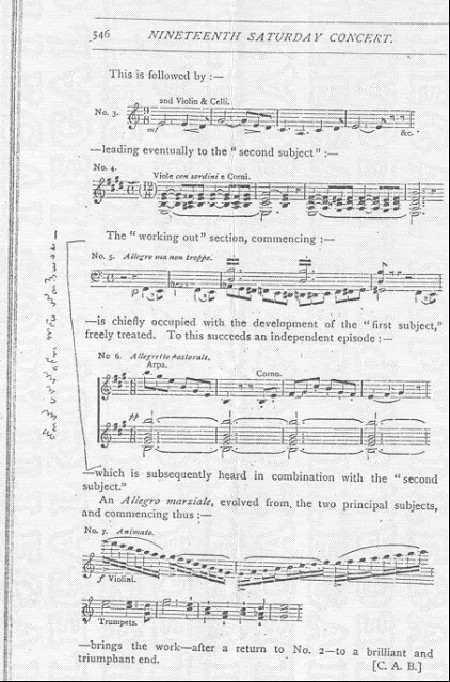

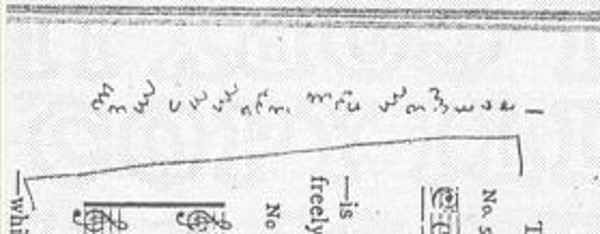

On April 10, 1886, Edward Elgar visited the Crystal Palace to attend a performance in honor of 75-year-old Franz Liszt, who was visiting England after an absence of many years. In the margin of his program Elgar made a cryptic notation:

What does it mean? Anthony Thorley suggested that it was a cipher representing the words GETS YOU TO JOY, AND HYSTERIOUS, where the last word is a portmanteau combining hysteria and mysterious. But that seems contrived, and in any case “this doesn’t fit!” writes Craig Bauer in Unsolved!, his history of ciphers. “Not only do repeated letters fail to line up with the same squiggles each time, but we don’t even have the right number of squiggles. The last six letters of the proposed decipherment have nothing to line up with.”

If Thorley is mistaken, then this fragment remains unsolved, like Elgar’s Dorabella cipher of 11 years later. Are the two messages related?