In the mid-1990s Jacques Jouet introduced “metro poems,” poems written on the Paris Métro according to a particular set of rules. He explained the rules in a poem:

There are as many lines in a metro poem as there are stations in your journey, minus one.

The first line is composed mentally between the first two stations of your journey (counting the station you got on at).

It is then written down when the train stops at the second station.

The second line is composed mentally between the second and the third stations of your journey.

It is then written down when the train stops at the third station.

And so on.

The poet mustn’t write anything down when the train is moving, and he mustn’t compose anything when the train is stopped. If he changes lines then he must start a new stanza. He writes down the poem’s last line on the platform of the final station.

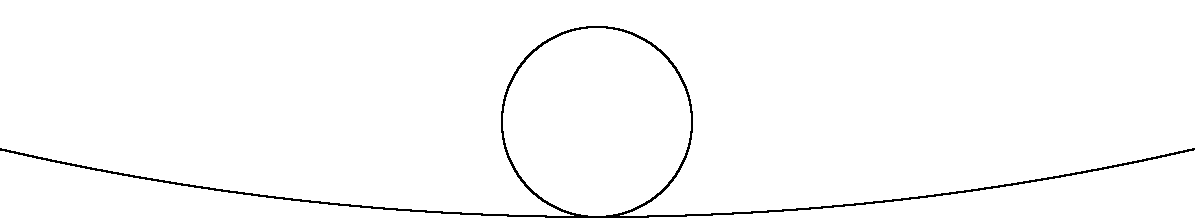

Jouet’s poem was itself composed in the Métro, according to its own rules. Presumably this type of writing could be done in any subway, but Marc Lapprand notes that the Paris system supports it unusually well: It’s dense, with 368 different stations, including 87 connecting points (or 293 nominal stations, including 55 connecting points) and a fairly short distance between them (543 meters, on average). The average run between two stations in Paris is a minute and a half, which means the poet has to think quickly in order to keep up.

Levin Becker, who tried the technique for his book 2012 Many Subtle Channels, found it surprisingly challenging: “It constrains the space around your thoughts, not the letters or words in which you will eventually fit them: you have to work to think thoughts of the right size, to focus on the line at hand without workshopping the previous one or anticipating the next.”

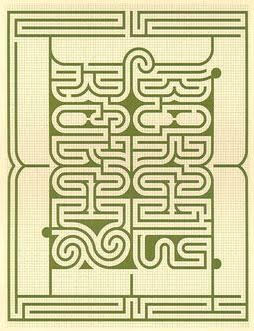

In April 1996 Jouet wrote a 490-verse poem while passing through every station in the Métro, following an optimized map laid out for him by a graph theorist. “At the end of those fifteen and a half hours,” he wrote, “I was very tired.”

(Jacques Jouet and Ian Monk, “Metro Poems,” AA Files 45/46 [Winter 2001], 4-14.)