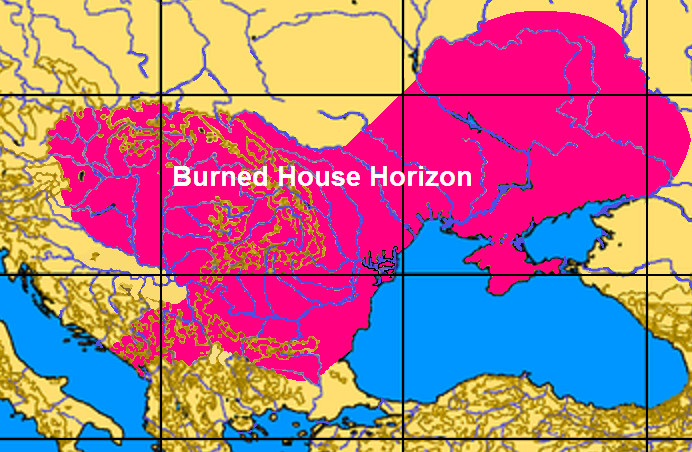

The Cucuteni-Trypillian culture of Neolithic Europe left behind a curious puzzle for archaeologists: It appears that, for more than a thousand years, the houses in every settlement were burned. It’s not clear why. Possibly the fires arose accidentally or through warfare, or possibly they were set deliberately. The extent of each fire must have been considerable, because the raw clay in the walls has been vitrified by intense heat, an effect that has not appeared in modern experiments with individual houses. But the reason for the phenomenon, and for its longevity, remains unknown.