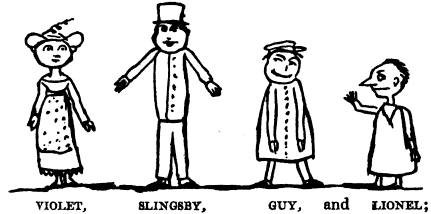

Once upon a time, a long while ago, there were four little people whose names were

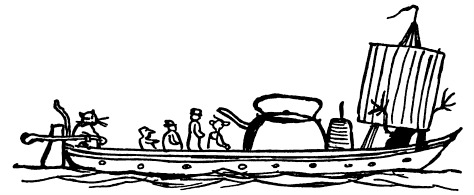

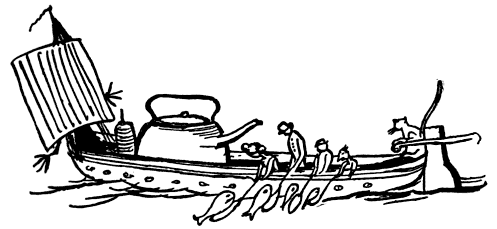

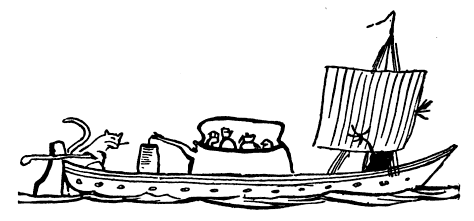

and they all thought they should like to see the world. So they bought a large boat to sail quite round the world by sea, and then they were to come back on the other side by land. The boat was painted blue with green spots, and the sail was yellow with red stripes: and, when they set off, they only took a small Cat to steer and look after the boat, besides an elderly Quangle-Wangle, who had to cook the dinner and make the tea; for which purposes they took a large kettle.

For the first ten days they sailed on beautifully, and found plenty to eat, as there were lots of fish; and they had only to take them out of the sea with a long spoon, when the Quangle-Wangle instantly cooked them; and the Pussy-Cat was fed with the bones, with which she expressed herself pleased, on the whole: so that all the party were very happy.

During the daytime, Violet chiefly occupied herself in putting salt water into a churn; while her three brothers churned it violently, in the hope that it would turn into butter, which it seldom if ever did; and in the evening they all retired into the tea-kettle, where they all managed to sleep very comfortably, while Pussy and the Quangle-Wangle managed the boat.

After a time, they saw some land at a distance; and, when they came to it, they found it was an island made of water quite surrounded by earth. Besides that, it was bordered by evanescent isthmuses, with a great gulf-stream running about all over it; so that it was perfectly beautiful, and contained only a single tree, 503 feet high.

When they had landed, they walked about, but found, to their great surprise, that the island was quite full of veal-cutlets and chocolate-drops, and nothing else. So they all climbed up the single high tree to discover, if possible, if there were any people; but having remained on the top of the tree for a week, and not seeing anybody, they naturally concluded that there were no inhabitants; and accordingly, when they came down, they loaded the boat with two thousand veal-cutlets and a million of chocolate-drops; and these afforded them sustenance for more than a month, during which time they pursued their voyage with the utmost delight and apathy.

— Edward Lear, “The Story of the Four Little Children Who Went Around the World,” from The Complete Nonsense Book, 1921