Letters to the Sydney Morning Herald during the planning of the Sydney Opera House:

“Faced with the nightmare illustrated in your columns, some 25th century Bluebeard’s lair, its ominous vanes pointed skywards apparently only for the purpose of discharging guided missiles or some latter-day nuclear Evil Eye, words fail.”

— W.H. Peters, Sydney, Jan. 31, 1957

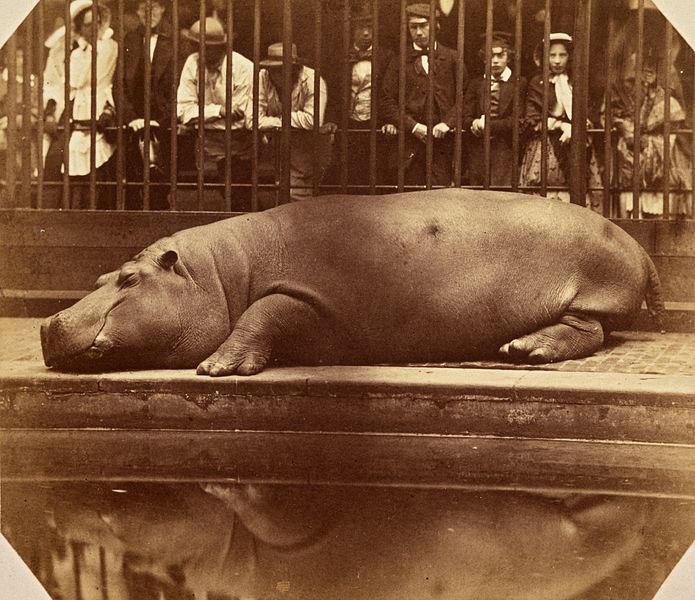

“To me, the winning design suggests some gargantuan monster which may have wandered over the land millions of years ago. It certainly is right out of place beside the dignity of the Harbour Bridge.”

— M. Rathbone, Kensington, Jan. 31, 1957

“This whale of a monument to the clever ugliness of ‘modern’ art will be a constant eyesore. Its over-finished roof with many curved surfaces all covered with white tiles will be a glaring monstrosity. Could not the suffering which it will cause be more equitably distributed by constructing the fins in such a way that they will act as giant megaphones and thus keep residents on the north supplied with the dying screams of melodramatic sopranos?”

— J.R.L. Johnstone Beecroft, Feb. 1, 1957

“With all respects to so-called modern art, I feel that the design is completely unbefitting our foreshores. Perhaps the judges had in mind the installation of a Big Dipper on the peak of the roof to help the opera company balance its budget.”

— Jack Zuber, Kingsgrove, Feb. 1, 1957

In 2003 Danish architect Jørn Utzon received the Pritzker Architecture Prize, architecture’s highest honour. The citation read, “There is no doubt that the Sydney Opera House is his masterpiece. It is one of the great iconic buildings of the 20th century, an image of great beauty that has become known throughout the world — a symbol for not only a city, but a whole country and continent.”