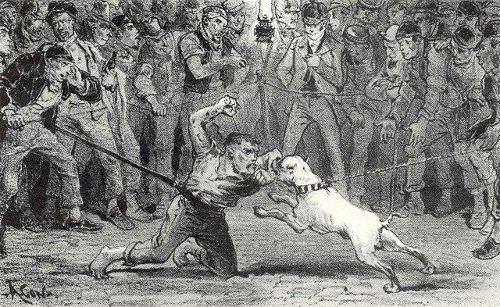

The New York Times carried an alarming item on July 28, 1874: “A Dog and Man Fight in England,” about a dwarf named Brummy who had undertaken to fight a bulldog on a wager, “without weapons and without clothes, except his trousers.” The fight took place in “a quiet house,” where the combatants were chained to opposite walls, and Brummy agreed to assume all fours throughout. The first to knock out the other for 60 seconds was to be declared the victor:

The man was on all fours when the words ‘Let go’ were uttered, and, making accurate allowance for the length of the dog’s chain, he arched his back, cat wise, so as just to escape its fangs, and fetched it a blow on the crown of its head that brought it almost to its knees. The dog’s recovery, however, was instantaneous; and before the dwarf could draw back, Physic made a second dart forward, and this time its teeth grazed, the biped’s arm, causing a slight red trickling. He grinned scornfully, and sucked the place; but there was tremendous excitement among the bull-dog’s backers, who clapped their hands with delight, rejoicing in the honour of first blood.

After 10 rounds of this “the bull-dog’s head was swelled much beyond its accustomed size; it had lost two teeth, and one of its eyes was entirely shut up; while as for the dwarf, his fists, as well as his arms, were reeking, and his hideous face was ghastly pale with rage and despair of victory.” But then “the dwarf dealt him a tremendous blow under the chin, and with such effect that the dog was dashed against the wall, where, despite all its master could do to revive it it continued to lie, and being unable to respond when ‘time’ was called, Brummy was declared to be victorious.”

The Times, which had picked up the story from the London Telegraph, noted that in the ensuing outrage the Home Secretary had directed the mayor of Hanley to investigate, and as no confirmation could be found, “there is a strong hope that, after all, the whole thing is a canard.” The Telegraph, however, “stands by its correspondent, and insists upon the truth of the report.”