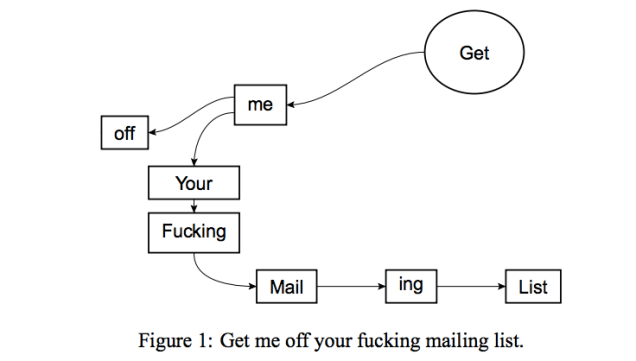

In 2014, after receiving dozens of unsolicited emails from the International Journal of Advanced Computer Technology, scientists David Mazières and Eddie Kohler submitted a paper titled “Get Me Off Your Fucking Mailing List.”

To Mazières’ surprise, “It was accepted for publication. I pretty much fell off my chair.”

The acceptance bolsters the authors’ contention that IJACT is a predatory journal, an indiscriminate but superficially scholarly publication that subsists on editorial fees. Mazières said, “They told me to add some more recent references and do a bit of reformatting. But otherwise they said its suitability for the journal was excellent.”

He didn’t pursue it. And, at least as of 2014, “They still haven’t taken me off their mailing list.”