Since its launch in 1991, arXiv, Cornell’s open-access repository of electronic preprints, has cataloged more than 2 million scientific papers.

In 2010, Caltech physicist David Simmons-Duffin created snarXiv, a random generator that produces titles and abstracts of imaginary articles in theoretical high-energy physics. Then he challenged visitors to distinguish real titles from fake ones.

After 6 months and 750,000 guesses in more than 50,000 games played in 67 countries, “the results are clear,” he concluded. “Science sounds like gobbledygook.” On average, players had guessed right only 59 percent of the time. Real papers most often judged to be fake:

- “Highlights of the Theory,” by B.Z. Kopeliovich and R. Peschanski

- “Heterotic on Half-Flat,” by Sebastien Gurrieri, Andre Lukas, and Andrei Micu

- “Relativistic Confinement of Neutral Fermions With a Trigonometric Tangent Potential,” by Luis B. Castro and Antonio S. de Castro

- “Toric Kahler Metrics and AdS_5 in Ring-Like Co-ordinates,” by Bobby S. Acharya, Suresh Govindarajan, and Chethan N. Gowdigere

- “Aspects of U_A(1) Breaking in the Nambu and Jona-Lasinio Model,” by Alexander A. Osipov, Brigitte Hiller, Veronique Bernard, and Alex H. Blin

- “Energy’s and Amplitudes’ Positivity,” by Alberto Nicolis, Riccardo Rattazzi, and Enrico Trincherini

Try it yourself.

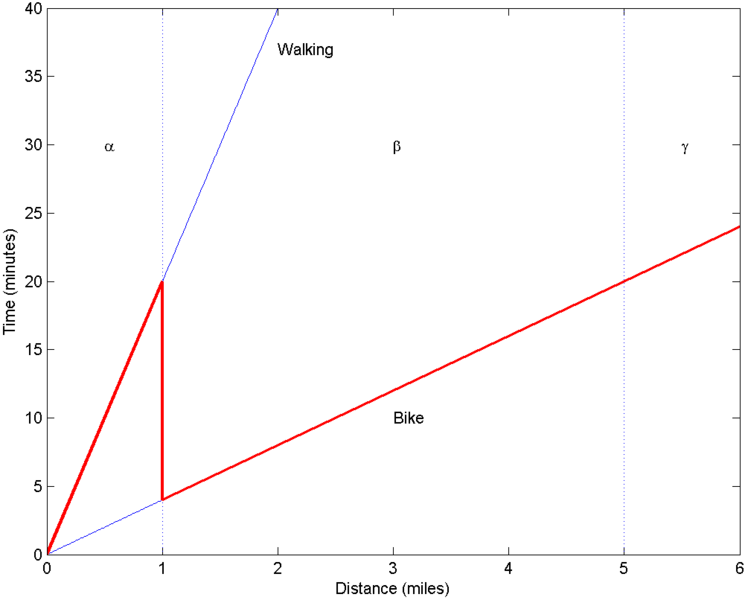

While we’re at it: SCIgen randomly generates research papers in computer science, complete with graphs, figures, and citations; and Mathgen generates professional-looking mathematics papers, with theorems, proofs, equations, discussion, and references.

(Via Andrew May, Fake Physics: Spoofs, Hoaxes and Fictitious Science, 2019.)