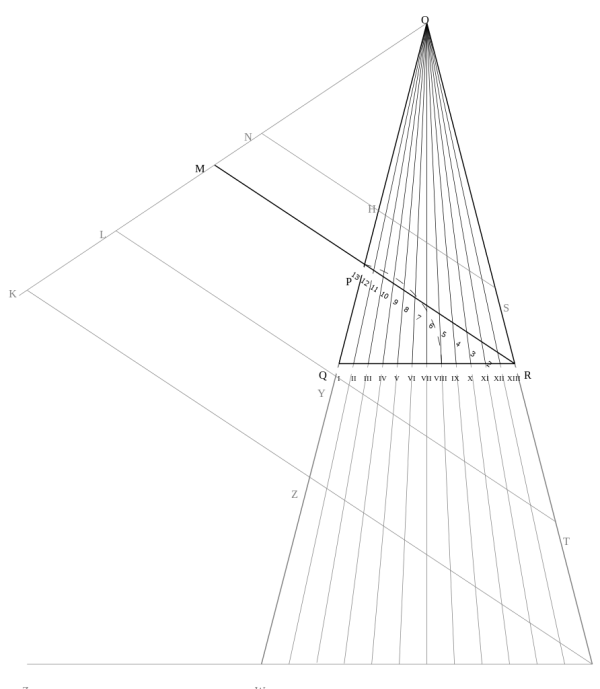

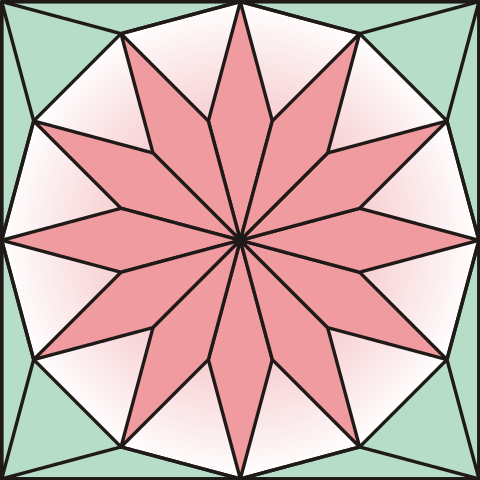

Hungarian mathematician József Kürschák offered this “proof without words” that a regular dodecagon inscribed in a unit circle has area 3. If the circle is inscribed in a square, the resulting figure can be tiled by triangles of two families — 16 equilateral triangles whose sides are equal to those of the dodecagon and 32 isosceles triangles with angles 15°-15°-150° and longest side 1. The area of the large square is 4, and the triangles that make up the dodecagon can be rearranged to fill 3 of its quadrants (see the video below). So the area of the dodecagon is 3/4 of 4, or 3.

(To see that the square and the dodecagon can be tiled as claimed, see Alexander Bogomolny’s discussion here.)

(Gerald L. Alexanderson and Kenneth Seydel, “Kürschak’s Tile,” Mathematical Gazette 62:421 [October 1978], 192-196.)