This card curiosity is attributed to Lewis Carroll.

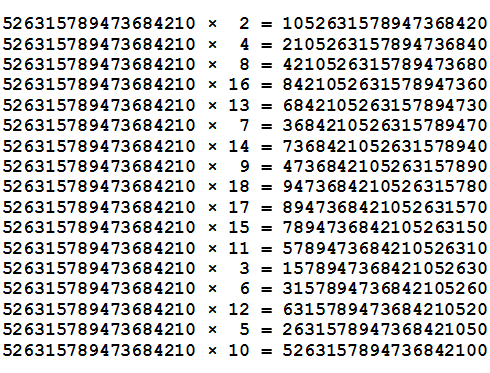

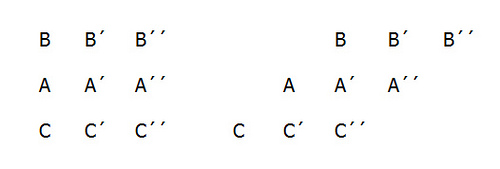

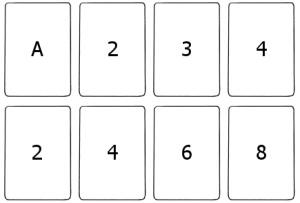

Lay down eight cards with these values:

Now add the values in each column, find a card of that value in the deck, and place it on top of the lower card. Aces count as 1, jacks as 11, queens as 12, and kings as 13. Thus in the first column 1 + 2 = 3, so you’d place a 3 on top of the 2.

When you’ve done all four columns, repeat the process, placing a 4 on the 3, etc. If a sum is more than 13, subtract 13 from it (for example, Q + 7 = 19 – 13 = 6). When you’ve exhausted the deck you’ll have four kings in the bottom row. Place each of these piles on the card above it, then take up the packs from right to left.

Turn the deck face down again and deal 13 cards in a circle, making note of which was dealt first. Counting from that card, deal 13 more cards, placing them on every second pile (that is, piles 2, 4, 6, etc.) and continuing around the circle until 13 are dealt. Then deal 13 more cards, one onto each third pile (piles 3, 6, 9, etc.), and finish by dealing the last 13 cards, one onto every fourth pile (4, 8, 12, etc.).

Each pile should now contain four cards. Take them up in order, starting with the first.

Now comes the payoff. Spell aloud A-C-E, dealing a card for each letter and turning the last one face up. It will be an ace. Continue with T-W-O, T-H-R-E-E, and so on up through J-A-C-K, Q-U-E-E-N, and K-I-N-G. In each case the last card will have the rank just spelled — and the full count will precisely exhaust the deck.

(From Robert Morrison Abraham, Winter Nights Entertainments, A Book of Pastimes for Everybody, 1932.)