Earth is the only planet not named after a god.

Earth is the only planet not named after a god.

Sherlock Holmes is an honorary fellow of the Royal Society of Chemistry.

“Holmes did not exist, but he should have existed,” society chief David Giachardi said in bestowing the award in 2002. “That is how important he is to our culture. We contend that the Sherlock Holmes myth is now so deeply rooted in the national and international psyche through books, films, radio and television that he has almost transcended fictional boundaries.”

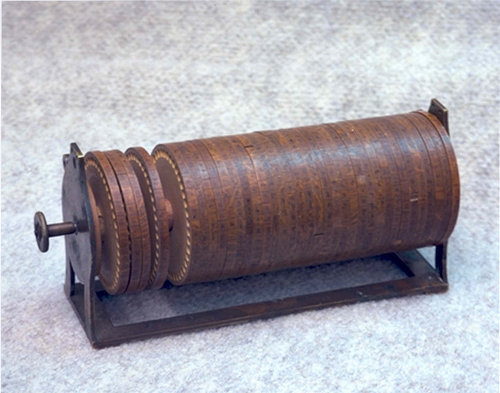

Thomas Jefferson, already absurdly accomplished by 1795, somehow found time to delve into cryptography, where he devised this cipher system. The letters of the alphabet are printed along the rim of each of 36 disks, which are stacked on an axle. One party rotates the disks until his message can be read along one of the 26 rows of letters, somewhat like a modern cylindrical bike lock. Now he can record the letters in any one of the other 25 rows and send that string safely to another party, who decodes it by reversing this procedure. If the message is intercepted, it’s useless even to someone who has the disks, because he must also know the order in which to stack them, and 36 disks can be stacked in 371,993,326,789,901,217,467,999,448,150,835, 200,000,000 different ways.

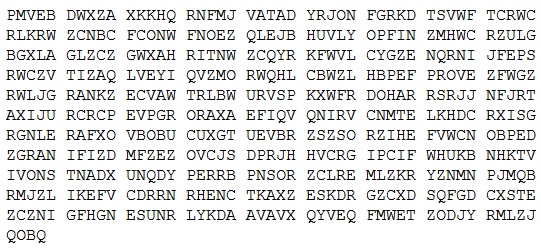

This is pretty robust. The cipher below, created in 1915 by U.S. Army cryptographer Joseph Mauborgne, has never been solved. “The known systems from this year (or earlier) shouldn’t be too hard to crack with modern attacks and technology,” writes NSA cryptologist Craig P. Bauer. “So, why don’t we have a plaintext yet? My best guess is that it used a cipher wheel” like Jefferson’s.

(L. Kruh, “A 77-year-old challenge cipher,” Cryptologia, 17(2), 172-174, 1993, quoted in Bauer’s Secret History: The Story of Cryptology, 2013.)

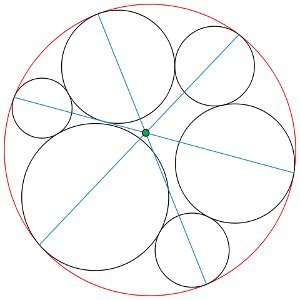

Squeeze six circles into a larger circle so that each is tangent to its two neighbors. Now the three lines drawn through opposite points of tangency will pass through the same point.

Remarkably, this wasn’t discovered until 1974.

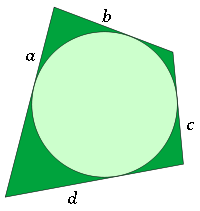

If a quadrilateral circumscribes a circle, then the sums of its opposite sides are equal.

Above, a + c = b + d.

Two travelers are transporting identical antiques. Unfortunately, the airline smashes both of them. The airline manager proposes that each traveler write down the cost of his antique, any value from $2 to $100. If both write the same number, the airline will pay this amount to both travelers. If they write different numbers, the airline will assume that the lower number is the accurate price; the low bidder will receive this amount plus $2, and the high bidder will receive this amount minus $2. If they can’t confer, what strategy should the travelers take in deciding how to bid?

At first Traveler A might like to bid $100, the maximum allowed. If his opponent does the same then they’ll both net $100. But A can do better than this: If B bids $100 and A bids $99 then A will come away with $101.

Unfortunately if B is rational then he’ll have the same insight and also bid $99. So A had better undercut him again and bid $98.

This chain leads all the way down to $2. If both travelers are perfectly rational then they’ll both bid (and make) $2, the minimum price.

But this seems very unlikely to happen in actual practice — in real life both travelers would likely make high bids and get high (though perhaps unequal) payoffs.

“All intuition seems to militate against all formal reasoning in the traveler’s dilemma,” wrote economist Kaushik Basu in propounding the problem in 1994. “There is something very rational about rejecting (2, 2) and expecting your opponent to do the same. … The aim is to explain why, despite rationality being common knowledge, players would reject (2, 2), as intuitively seems to be the case.”

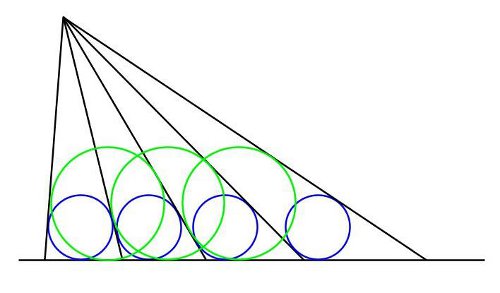

A Japanese geometry theorem from the Edo period: If the blue circles are equal, the green circles will be equal too.

This can be extended: Circles spanning three of these triangles will also be equal, and so on.

Jump into the sea and look up. The surface above you is dark except for a bright circle that follows you around like a portable skylight. This is Snell’s window: Because light is refracted as it enters the water, the 180-degree world above you is compressed into a tight 97 degrees.

Physicist Robert W. Wood was thinking of this effect when he created a new wide-angle lens in 1906. Fittingly, he called it the fisheye.

In 1990, Spanish philosopher Jon Perez Laraudogoitia submitted an article to Mind entitled “This Article Should Not Be Rejected by Mind.” In it, he argued:

They published it. “This is, I believe, the first article in the whole history of philosophy the content of which is concerned exclusively with its own self, or, in other words, which is totally self-referential,” Laraudogoitia wrote. “The reason why it is published is because in it there is a proof that it should not be rejected and that is all.”

In 1964 Canadian writer Graeme Gibson bought a parrot in Mexico. The bird, which Gibson named Harold Wilson, was bright and affectionate at first, but he seemed to grow lonely in the dark Canadian winter, so in the spring Gibson made arrangements to donate him to the Toronto Zoo. At the aviary Gibson carried Harold into the cage that had been prepared for him, placed him on a perch, said his goodbyes, and turned to go.

“Then Harold did something that astonished me. For the very first time, and in exactly the voice my kids might have used, he called out ‘Daddy!’ When I turned to look at him he was leaning towards me expectantly. ‘Daddy’, he repeated.

“I don’t remember what I said to him. Something about him being happier there, that he’d soon make friends. The kind of things you say to kids when you abandon them at camp. But outside the aviary I could still hear him calling ‘Daddy! Daddy!’ as we walked away. I was shattered to discover that Harold knew my name, and that he did so because he’d identified himself with my children.

“I now believe he’d known it all along, but was using it — for the first time — out of desperation. Both Konrad Lorenz and Bernd Heinrich mention instances of birds calling out the private names of intimates when threatened by serious danger. I am no longer surprised by such information. We think of our captive birds as our pets, but perhaps we are theirs as well.”

(From Gibson’s Perpetual Motion, 1982.)