512 × 1953125 = 1000000000

262144 × 3814697265625 = 1000000000000000000

8589934592 × 116415321826934814453125 = 1000000000000000000000000000000000

512 × 1953125 = 1000000000

262144 × 3814697265625 = 1000000000000000000

8589934592 × 116415321826934814453125 = 1000000000000000000000000000000000

Dr. Franklin had a party to dine with him one day at Passy, of whom one-half were Americans, the other half French, and among the last was the Abbé Raynal. During the dinner he got on his favorite theory of the degeneracy of animals, and even of man in America, and urged it with his usual eloquence. The Doctor, at length, noticing the accidental stature and position of his guests at table, ‘Come,’ says he, ‘M. l’Abbé, let us try this question by the fact before us. We are here one-half Americans and one-half French, and it happens that the Americans have placed themselves on one side of the table, and our French friends are on the other. Let both parties rise, and we will see on which side nature has degenerated.’ It happened that his American guests were Carmichael, Harmer, Humphreys, and others of the finest stature and form; while those on the other side were remarkably diminutive, and the Abbé himself particularly, was a mere shrimp. He parried the appeal by a complimentary admission of exceptions, among which the Doctor himself was a conspicuous one.

— Thomas Jefferson, quoted in James Parton, Life and Times of Benjamin Franklin, 1864

In 1964, as the Apollo program prepared to land a man on the moon, it received unexpected news from Zambia. “I’ll have my first Zambian astronaut on the moon by 1965,” announced Edward Mukaka Nkoloso, a grade-school science teacher and director-general of the Zambian National Academy of Space Research.

“We are using our own system, derived from the catapult,” he explained. It would fire a 10-foot aluminum and copper rocket that would carry 10 Zambian astronauts ultimately to Mars.

“I’m getting them acclimatized to space travel by placing them in my space capsule every day. It’s a 40-gallon oil drum in which they sit, and I then roll them down a hill. This gives them the feeling of rushing through space. I also make them swing from the end of a long rope. When they reach the highest point, I cut the rope — this produces the feeling of free fall.”

Unfortunately, “I’ve had trouble with my spacemen and spacewomen,” Nkoloso complained. “They won’t concentrate on spaceflight; there’s too much lovemaking when they should be studying the moon. Matha Mwamba, the 17-year-old girl who has been chosen to be the first woman on Mars, has also to feed her 10 cats, who will be her companions on her long space flight.”

The U.N. denied the £700 million Nkoloso needed “to really get going,” but his enthusiasm remained undiminished. In 1968 he congratulated the returning Apollo 8 team but urged: “Let us make a Zambian rocket today. We shall never be content to remain behind other races. This is our heavenly destiny, our natural ambition and cultural hegemony.”

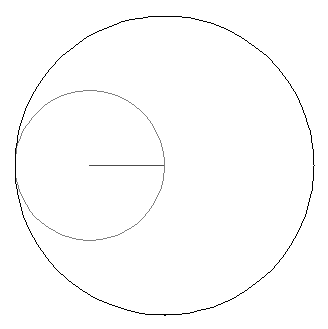

Suppose we set a small circle rolling around the interior of a large circle of twice its diameter. If we follow a point on the small circle, what pattern will it draw?

By Royal V. Heath:

12 + 43 + 65 + 78 = 87 + 56 + 34 + 21

That’s not terrifically impressive on its face. But:

At the start of her career, NIH immunologist Polly Matzinger disliked writing in the passive voice and felt too insecure to adopt the first person. So she listed her dog, Galadriel Mirkwood, as a coauthor and wrote as “we.”

Their paper was published in 1978 in the Journal of Experimental Medicine. When the editor learned Galadriel’s species, he barred Matzinger from his pages for the rest of his life.

Do men have more sisters than women do? Intuitively it seems they must. In a family with two children, a boy and a girl, the boy has a sister but the girl doesn’t. In a family with four children, two boys and two girls, each boy has two sisters but each girl has one. It seems inevitable that, on average, men must have more sisters than women.

But it isn’t true. There are four possible two-child families, all equally likely: BB, BG, GB, GG. Half of the children in these families have a sibling of the same sex, and half have a sibling of the opposite sex. This observation can be extended to larger families. So men have the same number of sisters as women.

Cut the Knot has a good discussion of the statistics, including a javascript simulator.

If I have two children, there’s a 50 percent chance that I’ll have a boy and a girl.

But if I have four children, the chance that I’ll have an equal number of boys and girls drops to 6 in 16, or 37.5 percent.

This trend continues — as the number of offspring rises, the chance of having precisely the same number of boys and girls drops:

2 children: 50 percent

4 children: 37.5 percent

8 children: 27.34375 percent

16 children: 19.6380615 percent

32 children: 13.9949934 percent

64 children: 9.9346754 percent

128 children: 7.0386092 percent

This is worrying. Does it mean that in a large population Jacks might drastically outnumber Jills?

No. As the population grows, the distribution assumes the shape of a normal bell curve concentrated near 1/2. So while the chance of precise parity drops, the chance that a large population will have approximately equal numbers of girls and boys actually increases, as we’d expect.

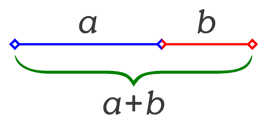

The golden mean is quite absurd;

It’s not your ordinary surd.

If you invert it (this is fun!),

You’ll get itself, reduced by one;

But if increased by unity,

This yields its square, take it from me.

— Paul S. Bruckman, The Fibonacci Quarterly, 1977