In 1953, 150 golfers participated in a “Golden Ball” competition in which they teed off at the first tee at Cill Dara Golf Club in Kildare, Ireland, and holed out at the 18th hole at the Curragh, about 5 miles away. A prize of £1 million was offered for a hole in one, which would have been well earned, as the distance is 8,800 yards.

In The Book of Irish Golf, John Redmond writes, “The hazards to be negotiated included the main Dublin-Cork railway line and road, the Curragh racecourse, Irish army tank ranges and about 150 telephone lines.” The trophy went to renowned long hitter Joe Carr, who covered the distance in 52 shots.

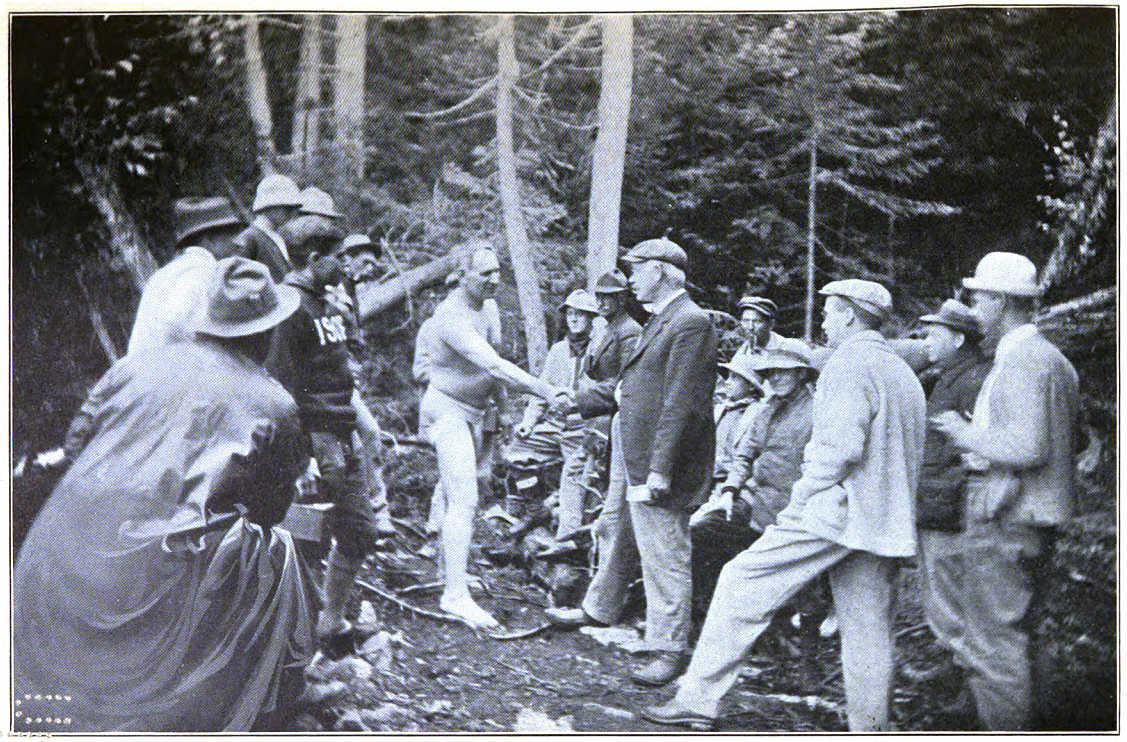

In 1920, Rupert Lewis and W. Raymond Thomas played over 20 miles of countryside from Radyr Golf Club near Cardiff, Wales, to Southerndown Golf Club at Ewenny, near Bridgend. Most onlookers guessed that they’d need at least 1,000 strokes, but they completed the journey in 608, playing alternate strokes. “At one time, the pair had to wade knee deep to ford a river,” writes Jonathan Rice in Curiosities of Golf, “but dried out by jumping a hedge while being chased by a bull.”

Inspired by the P.G. Wodehouse story “The Long Hole,” eight members of the Barnet Rugby Hackers Golf Club played 23 miles across Ayrshire in 1968, from Prestwick, the site of the first Open Championship, to Turnberry, the site of that year’s event. They lost “only” 50 or 60 balls while negotiating “a holiday camp, a dockyard, a stately home, a croquet lawn, several roofs, the River Doon,” and another bull, for a final score of 375 to 385.

N.T.P. Murphy gives a few more in A Wodehouse Handbook: In 1913 two golfers played 26 miles from Linton Park near Maidstone to Littleston-on-Sea in 1,087 strokes; Doe Graham played literally across country in 1927, from Florida’s Mobile Golf Club to Hollywood, a distance of 6,160,000 yards (I don’t have the final score, but he’d taken 20,000 strokes by the time he reached Beaumont, Texas); and Floyd Rood played from the Atlantic to the Pacific in 1963 in 114,737 shots.

The object of golf, observed Punch in 1892, “is to put a very small ball into a very tiny and remotely distant hole, with engines singularly ill adapted for the purpose.”

03/25/2017 UPDATE: Reader Shane Bennett notes that Australia’s Nullarbor Links claims to be the world’s longest golf course — players drive from Ceduna in South Australia to Kalgoorlie in Western Australia, stopping periodically to play a hole. Par for the 18 holes is only 73, but the course stretches over 1,365 kilometers. (Thanks, Shane.)