Oddities

Going Places

From the Strand, May 1899:

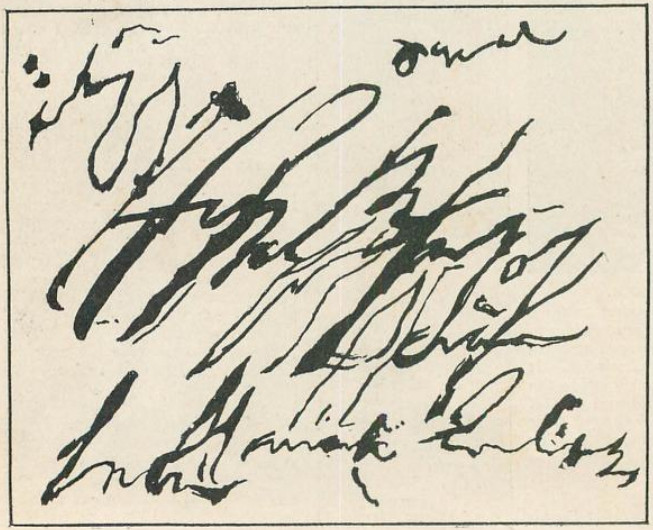

Our next photograph is a facsimile of an address on a letter that found its way from Spain to the G.P.O., St. Martin’s-le-Grand. Remarkable as it may seem, this specimen of handwriting was deciphered by ‘the blind man of St. Martin’s,’ and the letter safely reached its destination. It is addressed to the ‘Spanish Ambassador (or Embassy), London.’

(The “blind men” were “the decipherers of illegible and imperfect addresses” in the returned letter office of the General Post Office. Further examples.)

The Vista Paradox

In Bologna, the former convent of San Michele in Bosco contains a 162-meter hallway that’s “aimed” at the Asinelli tower 1,407 meters from the window. This produces an odd effect: As you move north along the hallway toward the window, you’re approaching the tower, yet it seems to shrink. This is because the retinal size of the window’s aperture increases enormously as you approach it, while the retinal size of the distant tower remains relatively unchanged.

Similarly, as you back away from the window the tower seems to grow and draw closer, because the “shrinking” window shuts out the panorama, leaving only the tower in view. The illusion was first reported on a 1714 map by Paolo Battista Baldi of the University of Bologna.

The city contains a second “vista paradox” in the hermitage of Ronzano, where another long hallway is oriented toward the Sanctuary of San Luca 1,970 meters away. The Sanctuary seems to shrink as one approaches the frame and to grow as one retreats.

Dream Weaving

Pat Ashforth and Steve Plummer make knitted illusions. When it’s viewed from the front, each piece presents only a series of unremarkable stripes, but when it’s viewed obliquely, an image emerges.

Here’s an introduction to the technique, and here are some patterns.

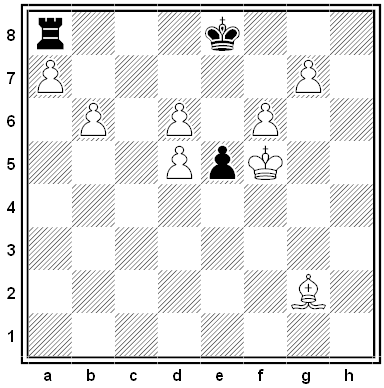

A Hazy Mate

Raymond Smullyan presented this oddity in his Chess Mysteries of Sherlock Holmes in 1980. Suppose we come upon this abandoned chess game. Can White mate in two moves? The answer seems to be yes. If Black can’t castle, then White can play 1. Ke6 and then promote his g-pawn, giving mate. If Black can castle, that means that neither his king nor his rook has yet moved, and hence he must just have moved his pawn to e5. That permits White to capture the pawn en passant. Now if Black castles then 2. b7 is mate, and if he plays any other move then the g-pawn promotes. Either way, White mates Black on his second move.

But that’s odd. We’ve decided that a mate in two exists, but we can’t show it — and we don’t even know how White commences!

(F. Alexander Norman, “Classicists and Constructivists: A Dilemma,” Mathematics Magazine 62:5 [December 1989], 340-342. See Donkey Sentences.)

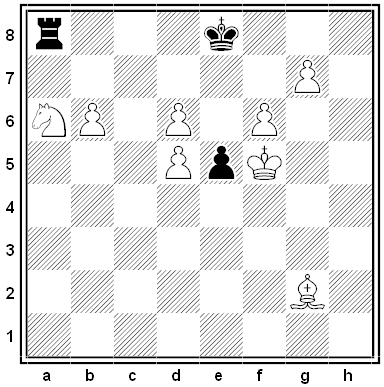

02/17/2025 UPDATE: Reader Eugene Kruglov points out that 1. Ke6 works in Smullyan’s position whether or not Black castles — if he does, then 2. a8=Q is mate. The position below works as Smullyan intended — when Black castles, only the en passant capture leads to mate in two. (Thanks, Eugene.)

Narrow Meaning

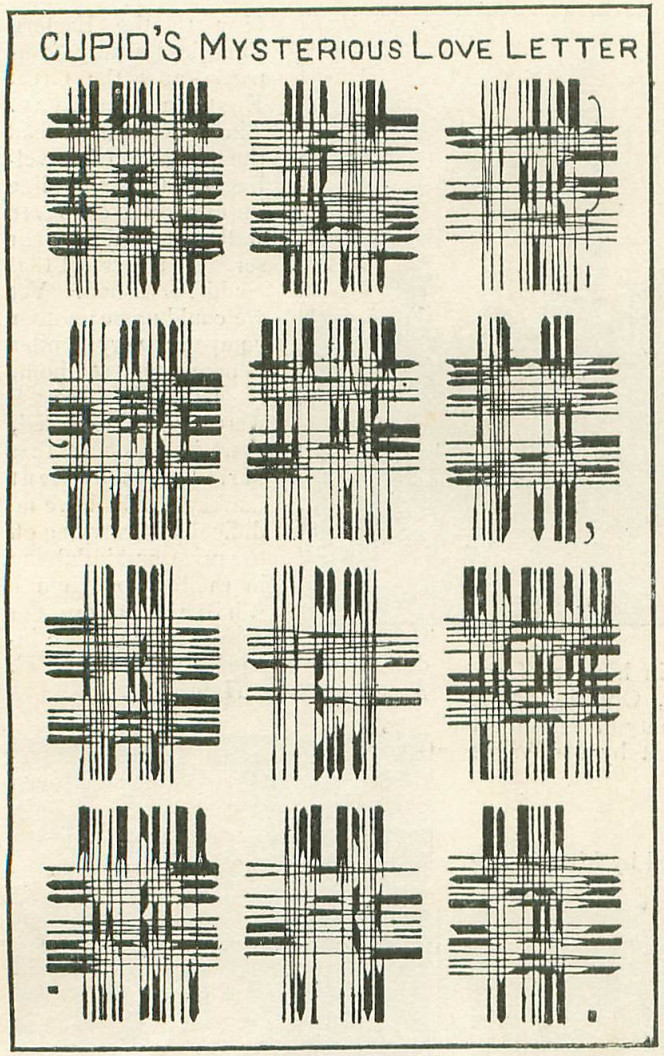

Reader J. William Hook submitted this curiosity to the Strand in August 1899. Holding the page level with the eyes foreshortens the characters and reveals a love poem:

Art thou not dear unto my heart?

Oh, I search that heart and see

And from my bosom tear the part

That beats not true to thee.

But to my bosom thou art dear,

More dear than words can tell,

And if a fault be cherished there,

‘Tis loving thee too well.

There seems to have been a little vogue for this kind of thing — C. Field submitted a similar image three months later.

Some Lost Snowmen

In his Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects (1550), Giorgio Vasari notes that in January 1494, while Michelangelo was working on his first full-scale stone figure, “there was a heavy snowfall in Florence and Piero de’ Medici, Lorenzo’s eldest son … wanting, in his youthfulness, to have a statue made of snow in the middle of his courtyard, remembered and sent for Michelangelo and had him make the statue.”

A heavy snowfall did occur that month: One chronicler wrote, “There was the severest snowstorm in Florence that the oldest people living could remember.” And it was a tradition on such occasions for outstanding artists to sculpt large snow figures, including the Marzocco, the heraldic lion that is the city’s symbol. But “What snow figure Michelangelo fashioned is not known,” writes critic Georg Brandes, “only that it stood in the courtyard of the Palazzo Medici.”

Seventeen years later, Brussels residents protested the wealthy Habsburgs by building 110 satirical snowmen, more than half of which were said to be pornographic. There’s no visual record of that, either. It’s known as the Miracle of 1511.

Academia

Caprices of Oxford dons, recounted in Maurice Bowra’s Memories: 1898-1939:

“In his quiet way [Wadham College Warden Joseph Wells] had an impressive authority, and it was told that once, when he heard a fearful row in the back quad, he walked up in the dark and said, ‘If you don’t stop at once, I shall light a match.’ They stopped.”

“[Oxford administrator Benjamin Parsons] Symons never admitted that he was wrong. An undergraduate was found drunk, and Symons abused another, quite innocent man for it, who said that his name was not that by which Symons had called him, but Symons would not admit it. ‘You’re drunk still. You don’t even know your own name. Go to your room at once.'”

“[Philosophy tutor Frank] Brabant kept a car and drove it badly, even by academic standards, which, from myopia, or self-righteousness, or loquacity, or absorption in other matters, are notoriously low. Once when I was with him, he drove straight into a cow and knocked it down, fortunately without damage. When the man in charge of it said quite mildly, ‘Look out where you are going,’ Brabant said fiercely, ‘Mind your own business,’ and drove on.”

See Metathesis.

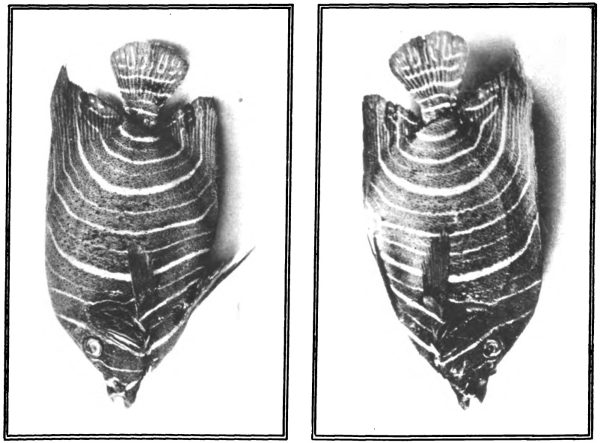

“A ‘Religious’ Fish”

Describing this fish (Holocanthus Alternaus), which was caught off Zanzibar, a correspondent of the ‘Times of India’ wrote: ‘… On the one side of the tail are the words, La-ilaha-illa Allah’ — ‘There is no God but God.’ On the other side, ‘Shan Allah’ — ‘God’s Work,’ or ‘An Act of God.’ … Many of our readers who know Arabic will be able to see for themselves from this untouched photograph that the fish is a devout Moslem.’ We have shown the photographs to an expert in this country, who informs us that the letters are certainly intended to represent Arabic characters, but that there is nothing sufficiently distinguishable to enable it to be said that they mean what they are alleged to mean. A further opinion is expressed that the ‘inscriptions’ may not be genuine.

— Illustrated London News, Dec. 28, 1929

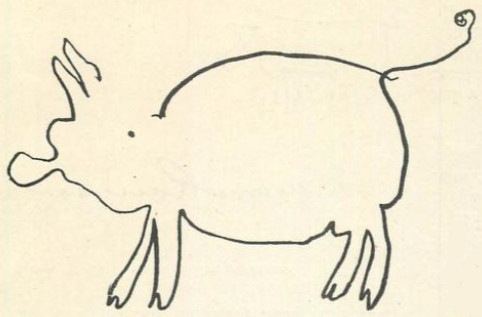

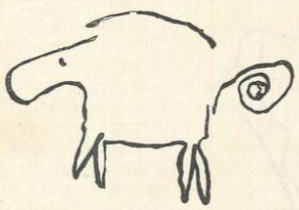

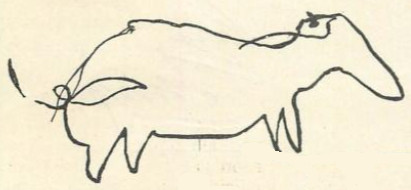

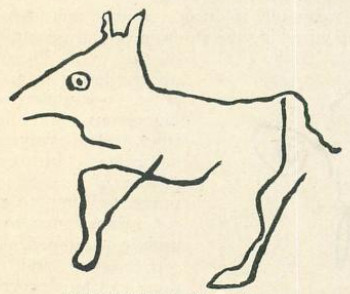

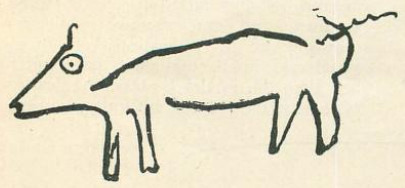

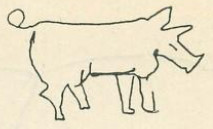

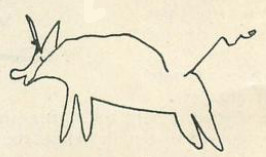

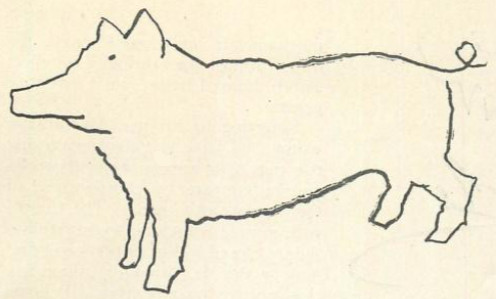

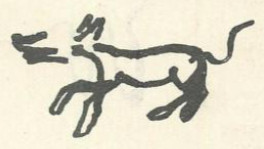

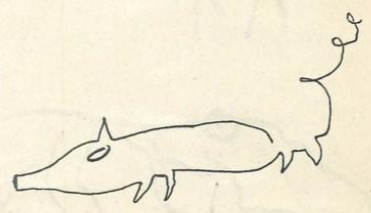

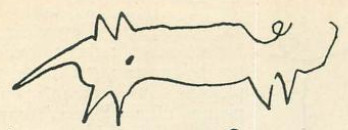

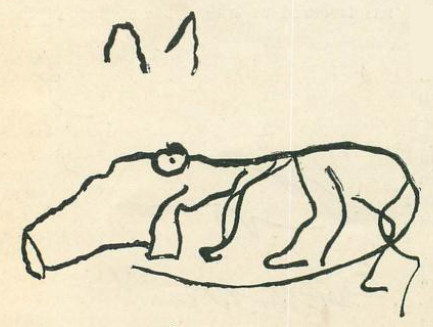

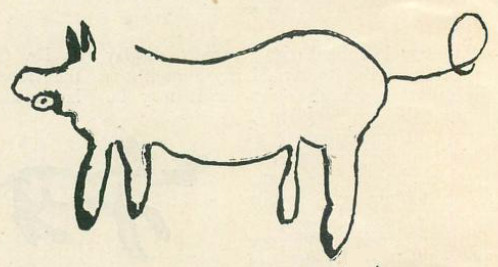

Pigs Penned

In 1899 the Strand invited 13 British celebrities to draw a pig with their eyes closed.

Field Marshal Frederick Sleigh Roberts:

Judge Sir Francis Jeune:

Mary Jeune, Baroness St Helier:

Hugh Jermyn, Bishop of Brechin:

Astronomer Sir Robert Ball:

Chemist William Ramsay:

Stage actor Henry Irving:

Illustrator Sir John Tenniel:

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle:

Novelist Walter Besant:

Organist Sir Frederick Bridge:

Inventor Hiram Maxim:

Magician Nevil Maskelyne:

(Illustrator Harry Furniss says the trick is to use your free hand as a guide.)