“What happens to the hole when the cheese is gone?” — Bertolt Brecht

“What happens to the hole when the cheese is gone?” — Bertolt Brecht

The soul, aspiring, pants its source to mount,

As streams meander level with their fount.

That’s Robert Montgomery, in “The Omnipresence of the Deity.” Thomas Macaulay writes:

We take this to be, on the whole, the worst similitude the world. In the first place, no stream meanders, or can possibly meander level with its fount. In the next place, if streams did meander level with their founts, no two motions can be less like each other than that of meandering level and that of mounting upwards.

“Those who write clearly have readers,” wrote Camus. “Those who write obscurely have commentators.”

In 1892, J. McCullough, secretary of Scotland’s North Berwick Green Committee, wrote a little book called Golf in the Year 2000, in which a man falls asleep and wakes up in a technologically advanced future. It was largely overlooked at the time but was rediscovered in the millennium, when the future world arrived.

On the links McCullough largely missed the mark — he thought we’d have golf clubs that automatically kept score, driverless carts, and jackets that yelled “Fore!”

But in the wider world he accurately predicted:

McCullough had said he was simply trying to imagine “what we are coming to if things go on as they are doing.” It’s a pity he didn’t write a sequel — one wonders what he might have foreseen in our own future.

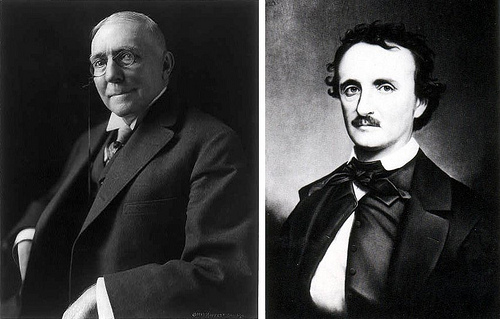

Convinced that the public would accept anything from an established author, James Whitcomb Riley bet his friends that he could prove it. He composed a poem entitled “Leonanie” in the style of Edgar Allan Poe and published it in the Kokomo, Ind., Despatch on Aug. 2, 1877:

Leonanie–angels named her;

And they took the light

Of the laughing stars and framed her

In a smile of white;

And they made her hair of gloomy

Midnight, and her eyes of bloomy

Moonshine, and they brought her to me

In the solemn night.

And so on. An accompanying article explained that the poem had been discovered on the blank flyleaf of an old book, and the conspirators scribbled it into a dictionary in case anyone asked to see it.

After the poem was published, Riley wrote a critique in the Anderson Democrat casting doubt on Poe’s authorship. But to his horror his poem was championed by critics and picked up in newspapers nationwide, and soon a Boston publishing house began asking for the original manuscript. The group finally confessed when a rival paper threatened to expose the hoax.

Riley won his bet, but ironically he went on to become a bestselling poet himself, writing in an Indiana dialect distinctive enough to invite lampoons of its own. Whether any of these has been passed off as real is unknown — but it would be poetic justice.

Sylvia Plath committed suicide in Yeats’ house.

She had taken a flat at 23 Fitzroy Road in London, where Yeats had lived from 1867 to 1874. She told her mother that she felt “Yeats’ spirit blessing me.”

See Noisy Neighbors.

The diary of Elizabethan lawyer John Manningham reveals a Bugs-Bunny-like episode from the life of William Shakespeare. When Richard Burbidge was playing Richard III, a female audience member “greue soe farr in liking wth him” that she asked him to visit her that evening using the name Richard III. Shakespeare overheard this, beat Burbidge to the lady’s house and “was intertained.” When word came that Richard III was at the door, Manningham says, Shakespeare sent the reply that “William the Conqueror came before Richard III.”

Is it true? Who cares?

“I always find it more difficult to say the things I mean than the things I don’t.” — Somerset Maugham

After cataloging her disappointment with Europe, Asia, and Australia, xenophobic travel writer Favell Lee Mortimer finished her world survey with Far Off, Part II: Africa and America Described (1854). What did she discover about the intriguing people and exotic customs of these remote continents?

“Washington is one of the most desolate cities in the world: not because she is in ruins, but for the opposite reason — because she is unfinished. There are places marked out where houses ought to be, but where no houses seem ever likely to be.”

Author Octavus Roy Cohen was visiting a friend in Colorado when the surprising word came that Cohen himself would be speaking at a men’s luncheon club in Denver. Bewildered, the two attended the luncheon and watched an impostor give a “splendid literary talk.”

After this, the program director announced a surprise guest — Edna Ferber. Cohen had always wanted to meet Ferber, but to avoid embarrassing the club he held his peace and watched his impostor trade compliments with the guest author.

On his next visit to New York, he called Ferber. “I’m Octavus Roy Cohen,” he said, “the man you thought you met recently in Denver –”

“What are you talking about?” she said. “I haven’t been in Denver in years.”