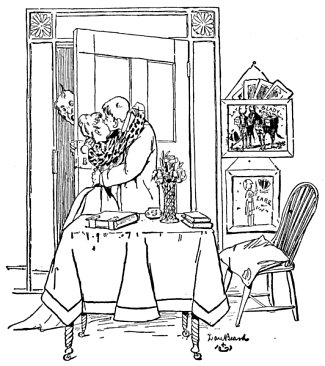

The earliest mention of baseball may be in Northanger Abbey, of all places:

… it was not very wonderful that Catherine, who had by nature nothing heroic about her, should prefer cricket, baseball, riding on horseback, and running about the country at the age of fourteen, to books.

Jane Austen wrote that passage in 1798, 41 years before Abner Doubleday supposedly invented the game in 1839. Evidence now suggests that “America’s game” evolved in England and was imported to the New World in the 18th century.

UPDATE: A reader alerts me that the town of Pittsfield, Mass., passed an ordinance in 1791 forbidding inhabitants from playing “Baseball” and certain other games near a new meeting house. This is believed to be the first written reference to baseball in North America. But a researcher at the Oxford English Dictionary tells me that the OED now has an example dating from 1748: “Now, in the winter, in a large room, they divert themselves at base-ball, a play all who are, or have been, schoolboys, are well acquainted with.” The letter writer was English, so, for the moment, England has the ball.