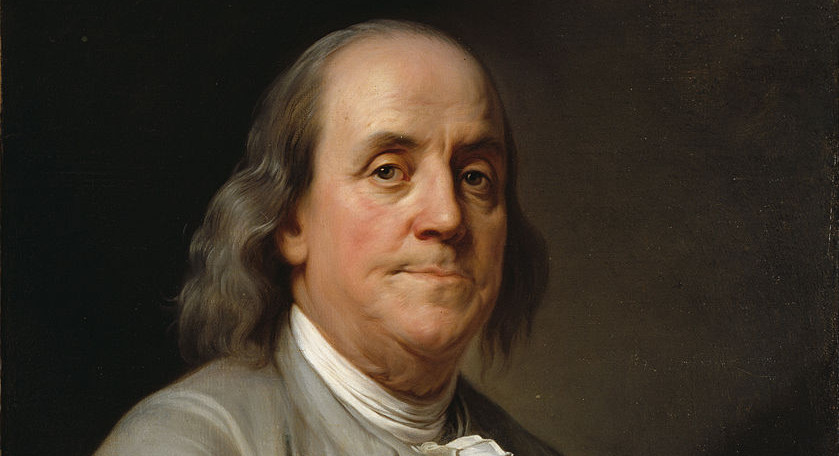

Ben Franklin used chess to learn Italian. From his autobiography:

I had begun in 1733 to study languages; I soon made myself so much a master of the French as to be able to read the books with ease. I then undertook the Italian. An acquaintance, who was also learning it, us’d often to tempt me to play chess with him. Finding this took up too much of the time I had to spare for study, I at length refus’d to play any more, unless on this condition, that the victor in every game should have a right to impose a task, either in parts of the grammar to be got by heart, or in translations, etc., which tasks the vanquish’d was to perform upon honour, before our next meeting.

“As we play’d pretty equally,” he wrote, “we thus beat one another into that language.”