I don’t know anything about this; it just popped up on the subreddit r/funny:

“Someone in the Netherlands has a sense of humor.”

06/02/2025 UPDATE: Oop, no, it’s at the Dudutki ethnographic museum in Minsk! (Thanks, Nick.)

I don’t know anything about this; it just popped up on the subreddit r/funny:

“Someone in the Netherlands has a sense of humor.”

06/02/2025 UPDATE: Oop, no, it’s at the Dudutki ethnographic museum in Minsk! (Thanks, Nick.)

In his later years Joseph Conrad became obsessed with the opening scene of an unwritten novel that he planned to set in an Eastern European state. “So vividly used he to describe this scene to me,” wrote his friend Richard Curle, “that at last it was as though I had been a witness to it myself”:

“In the courtyard of a royal palace, brilliantly lighted up as for a festival, soldiers are bivouacked in the snow. And inside the palace a fateful council is taking place and the destiny of the country is being decided.”

“I never learned anything more about this novel — I do not know how far Conrad had himself visualized the plot,” Curle wrote, “but as he pictured that opening scene one could almost feel the tension in the air and one almost seemed to be warming one’s hands with the soldiers around their blazing fire.”

(Richard Curle, The Last Twelve Years of Joseph Conrad, 1928.)

An odd detail from the autobiography of Bertrand Russell:

“The summers of 1903 and 1904 we spent at Churt and Tilford. I made a practice of wandering about the common every night from eleven till one, by which means I came to know the three different noises made by night-jars.”

He adds, “(Most people only know one.)” He says nothing more.

Occasionally, by coincidence, the gaps between words on a page of printed text will become aligned, producing “rivers” of white space that descend across multiple lines. These occur most commonly when the font is monospaced and justification is full. Because they’re distracting, these artifacts are generally discouraged; typographers sometimes view a printed page upside down in order to spot them.

In ordinary text long rivers are unlikely, but in 1988 Mark Isaak found the 12-line example above on page 277 of the Harvard Classics edition of Darwin’s The Voyage of the Beagle (squint to see it).

Fritzi Striebel offered a small collection of unusual rivers at the end of this article in the May 1986 issue of Word Ways.

Memorable passages from the pulp detective stories of Robert Leslie Bellem (1902-1968):

“From the doorway a roscoe said ‘Kachow!’ and a slug creased the side of my noggin. Neon lights exploded inside my think-tank. … She was as dead as a stuffed mongoose. … I wasn’t badly hurt. But I don’t like to be shot at. I don’t like dames to be rubbed out when I’m flinging woo at them.”

Sydney Smith wrote a recipe for salad dressing:

Two boiled potatoes, strained through a kitchen sieve,

Softness and smoothness to the salad give;

Of mordant mustard take a single spoon —

Distrust the condiment that bites too soon;

Yet deem it not, thou man of taste, a fault,

To add a double quantity of salt.

Four times the spoon with oil of Lucca crown,

And twice with vinegar procured from town;

True taste requires it, and your poet begs

The pounded yellow of two well-boiled eggs.

Let onions’ atoms lurk within the bowl,

And, scarce suspected, animate the whole;

And lastly in the flavoured compound toss

A magic spoonful of anchovy sauce.

Oh, great and glorious! oh, herbaceous meat!

‘Twould tempt the dying anchorite to eat.

Back to the world he’d turn his weary soul,

And plunge his fingers in the salad bowl.

In the late 19th century, such rhymes helped cooks to master recipes. When this one was reproduced in an 1871 cookbook, many committed it to memory.

“Life is the art of drawing sufficient conclusions from insufficient premises.” — Samuel Butler

philomath

n. a lover of learning; a scholar

noddary

n. a foolish act

fedifragous

adj. contract-breaking

subitaneous

adj. sudden

In Fredric Brown’s 1954 short short story “Experiment,” Professor Johnson displays a brass cube and proposes to send it backward in time. An identical cube appears in his time machine at 2:55, and Johnson announces that at 3:00 he will complete the transaction by sending his own cube 5 minutes into the past.

A friend asks: What would happen if he changed his mind and didn’t send it?

“An interesting idea,” says the professor. “I had not thought of it, and it will be interesting to try. Very well, I shall not …”

“There was no paradox at all. The cube remained.

“But the entire rest of the Universe, professors and all, vanished.”

“We went back to England together. When we arrived at the customs shed, Syrie said: ‘Always choose the oldest customs official. No chance of promotion.'” — Somerset Maugham, quoting his wife

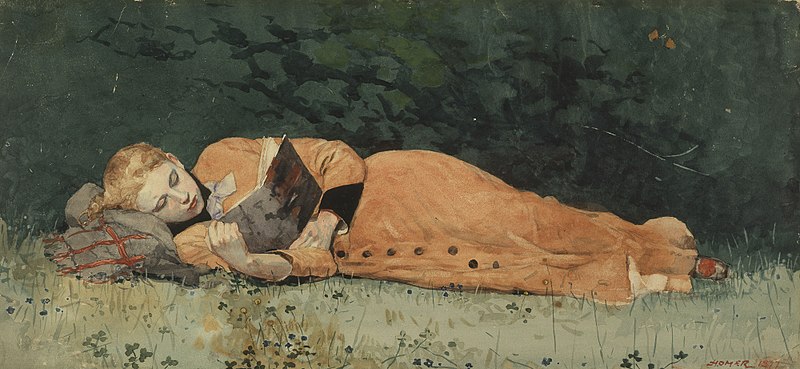

You see, when you learn to read you will be born again into another world and it is a pity to be born again so young. I should put off reading, if I were you. As soon as you learn to read you will not see anything again quite as it is. It will all the time be altered by what you have read and you will never be quite alone again. I should stay by yourself a bit longer if I were you.

— Rumer Godden, to her 4-year-old daughter Jane, 1939