“We went back to England together. When we arrived at the customs shed, Syrie said: ‘Always choose the oldest customs official. No chance of promotion.'” — Somerset Maugham, quoting his wife

Literature

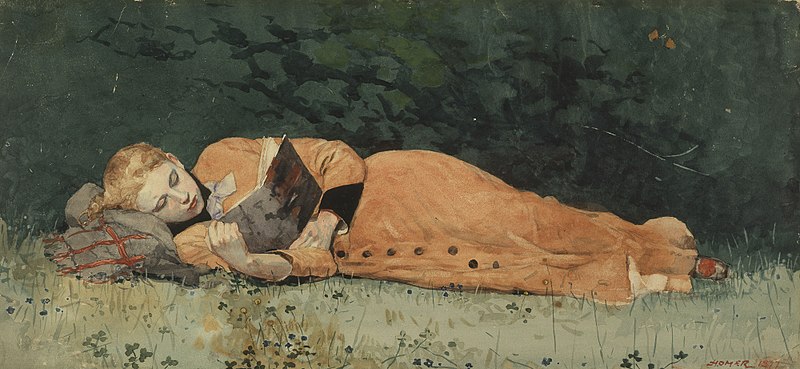

Another World

You see, when you learn to read you will be born again into another world and it is a pity to be born again so young. I should put off reading, if I were you. As soon as you learn to read you will not see anything again quite as it is. It will all the time be altered by what you have read and you will never be quite alone again. I should stay by yourself a bit longer if I were you.

— Rumer Godden, to her 4-year-old daughter Jane, 1939

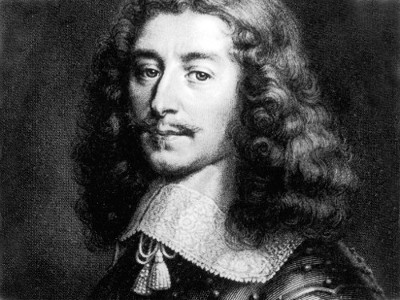

The Moralist

In his Table Talk, W.H. Auden says that La Rochefoucauld “simply says what one has always known.”

Robert Craft added, “Yes, but without him some of us would not have known that we knew.”

Credit

Dedication of P.G. Wodehouse’s 1926 book The Heart of a Goof:

To

My Daughter

Leonora

Without Whose Never-Failing

Sympathy and Encouragement

This Book

Would Have Been Finished

in

Half the Time

Misc

- It’s illegal to mispronounce Joliet.

- G.K. Chesterton left an unfinished poem titled Plakkopytrixphylisperadaulantiobatrix.

- Alms has no singular.

- The Spanish village Trasmoz has been cursed and excommunicated by the Catholic Church.

- “The wink was not our best invention.” — Ralph Hodgson

An Irish riddle: Yonder he is through the stream, a man without a coat, a man without a belt, a man of hard slender legs, it is my woe that I cannot run. Death.

Good Point

I can never get people to understand that poetry is the expression of excited passion, and that there is no such thing as a life of passion any more than a continuous earthquake, or an eternal fever. Besides, who would ever shave themselves in such a state?

— Lord Byron, letter to Thomas Moore, July 5, 1821

Unquote

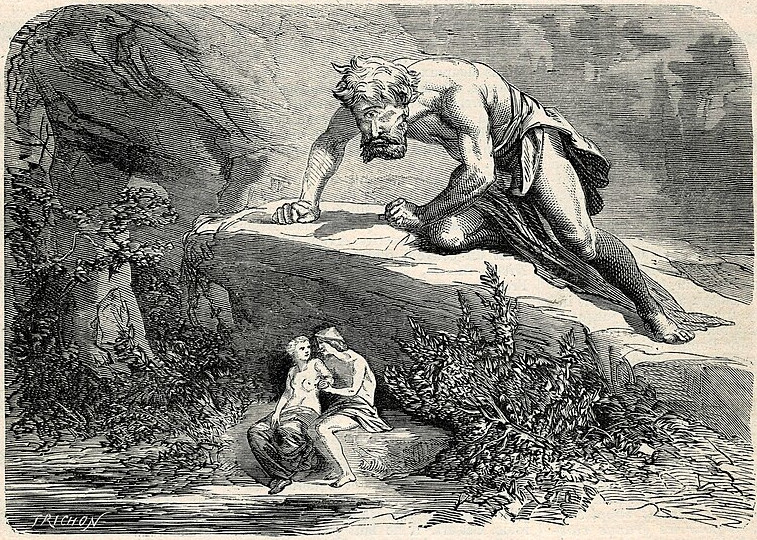

“A man who has not read Homer is like a man who has not seen the ocean. There is a great object of which he has no idea.” — Walter Bagehot

Apt

Writing in the Wall Street Journal about long sentences in literature, Laurie Winer offered her thoughts in a single sentence of 854 words:

In order to credit William Faulkner — as the Guinness Book of World Records does — with the longest sentence in literature, one must include, when counting the words in Faulkner’s erratically punctuated, loosely defined ‘sentences,’ lengthy italicized passages that echo what passes through a character’s mind; not to mention parentheses within parentheses; and long sentences connected to sentence fragments by dashes where periods, strictly speaking, should be; as well as run-on paragraphs that begin audaciously with a lower-case letter; and, while Guinness says the longest sentence is a 1,300-word tirade in Absalom, Absalom! there is, by liberal Faulknerian standards, a 1,928-word sentence (beginning ‘They both bore it as though in deliberate flagellant exaltation’) in that book which contains a 1,360-word parenthetical memory/thought that has within it at least 32 traditional sentences; so perhaps Faulkner should not be holding this title after all (from his London office a Guinness editor, Colin Smith, who says he has never seen Absalom, Absalom!, names as his source for the longest sentence entry the 1945 Bookmen’s Bedlam of Literary Oddities, a fustian collection of curiosa by bibliophile Walter Hart Blumenthal, which doesn’t mention Faulkner at all and instead gives the palm for sequential verbosity to Edward Phillips’s Preface to Theatrum Poetarium, written in 1675, for a 1,012-word sentence) even though others, including the writer Malcolm Cowley, cite another Faulkner sentence, found in the story ‘The Bear,’ as among the longest ever written; viz., in his introduction to the story in the 1946 The Portable Faulkner, Mr. Cowley calls this whopper, which begins ‘To him it was as though the ledgers in their scarred cracked leather bindings,’ a 1,800-word sentence when in fact it is, by the most liberal definition, a 1,600-word Faulknerian sentence, which is, under closer scrutiny, a 91-word sentence with no period followed by a new paragraph (indented) beginning with a lower-case letter that contains nothing but a 67-word sentence fragment that is followed by another paragraph fragment, etc. (even Albert Erskine, Faulkner’s editor at Random House, says of the long word group in ‘The Bear’: ‘New sentences begin whether the author puts a period there or not’), which may sound petty, but, if you’re going to call something the longest sentence, the term sentence must have some meaning or else what’s the point of bestowing the title (you may believe, as a confident New York City librarian told me, that the longest sentence in literature is the last 40,000 words of James Joyce’s Ulysses, which does contain two periods but which is really a poem, a chant, or free association that disintegrates at times to a point where it is unrecognisable as formal grammar or even as English (‘… I can see his face clean shaven Frseeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeefrong that train …’) and clings only, as the critic Roy K. Gottfried points out, to a morphemic structure, though while Joyce broke ground and freed his prose from the tyranny of syntax, he did not write a 40,000-word sentence) unless you give it to someone who actually wrote an extremely long sentence, as Marcel Proust did in his seven-volume masterpiece (first published as eight volumes, though Bookmen’s Bedlam calls it eleven and another reference book, Felton & Fowler’s Best, Worst, and Most Unusual, remembers it as sixteen — these record books seem to get none of the numbers right) Remembrance of Things Past, which contains in it a famous, perfect 958-word (in the C.K. Scott Moncrieff translation) sentence (it begins ‘Their honour precarious, their liberty provisional …’) that appears near the start of the fourth book, Sodome et Gomorrhe or, as it is known in English, Cities of the Plain, just after the narrator has witnessed a homosexual encounter between Jupien the tailor and the Baron de Charlus, an encounter that initiates a rumination on the part of our young hero, whose creator was himself a half-Jewish homosexual, on the tenuous situation of the homosexual in society and on how he is like the Jew in respect to the duplicity of his life, seeking to assimilate and yet compelled to remain different, permeated with the pain of the ever-present knowledge that, because of what he is, he gives cause to others to snub him, alienate him, or hate him, and of how this difference, shared by members on the highest and lowest rungs of society, bonds the ambassador to the felon, or the prince to the ruffian, for here is a sentence that does not suffocate the reader with its verbiage (as might the work of certain Teutotonic runners-up for the longest sentence, such as Thomas Bernhard or Hermann Broch); here is a sentence whose length befits its subject matter and its context in the whole; here is a sentence that can be parsed; here is a sentence that should be called the longest in literature (taking into account the possibility that there exist longer grammatical sentences — maybe some crank somewhere wrote a one-sentence book — but we are biased in favor of our titleholder’s also being a genius) by the Guinness people; so we suggest they change their Faulkner entry.

She followed this with a one-word paragraph: “Now.”

(Via Willard R. Espy’s The Word’s Gotten Out, 1989.)

Partiality

On hearing that Watership Down was a novel about rabbits written by a civil servant, Craig Brown wrote, “I would rather read a novel about civil servants written by a rabbit.”

Fair and Square

From Good-Bye to All That, poet Robert Graves’ 1929 account of his experiences in World War I:

Beaumont had been telling how he had won about five pounds’ worth of francs in the sweepstake after the Rue du Bois show: a sweepstake of the sort that leaves no bitterness behind it. Before a show, the platoon pools all its available cash and the survivors divide it up afterwards. Those who are killed can’t complain, the wounded would have given far more than that to escape as they have, and the unwounded regard the money as a consolation prize for still being here.

In 2003, the Journal of Political Economy reprinted this paragraph with the title “Optimal Risk Sharing in the Trenches.”