diffidation

n. a severing of peaceful relations

clarigation

n. a recital of wrongs before declaring war

diffidation

n. a severing of peaceful relations

clarigation

n. a recital of wrongs before declaring war

The Swedish pop group Caramba has an odd claim to fame — their eponymous 1981 album consists entirely of nonsense lyrics. No one’s even sure who was in the band — the album sleeve lists 13 members, all using pseudonyms. It was produced by Michael B. Tretow, who engineered ABBA’s records, and singer Ted Gärdestad contributed some vocals, but these are the only two participants who have been named.

The band broke up (apparently) after the first album, so we’ll never get more of this. Here are the lyrics to the single “Hubba Hubba Zoot Zoot”:

Hubba hubba zoot zoot

Num

Deba uba zat zat

Num

A-hoorepa hoorepa a-huh-hoorepa a-num num

A-num

Hubba hubba zoot zoot

Num

Deba uba zat zat

Num

A-hoorepa hoorepa a-huh-hoorepa a-num num

A-num

Hubba hubba zoot zoot

Deba uba zat zat a-num num

Hubba hubba zoot zoot

Deba uba zat zat a-num num

A-hoorepa hoorepa a-huh-hoorepa a-num num

A-hoorepa hoorepa

HAH

A-huh-hoorepa a-num num

A-num

Hubba hubba zoot zoot

Deba uba zat zat a-num num

Hubba hubba zoot zoot

Deba uba zat zat a-num num

A-hoorepa hoorepa a-huh-hoorepa a-num num

A-hoorepa hoorepa a-huh-hoorepa

HAH

A-num num

A-num

Hubba hubba zoot zoot

A-huh zoot a-huh

Deba uba zat zat a-num num

Hubba hubba zoot zoot

Deba uba zat zat a-num num

A-hoorepa hoorepa a-huh-hoorepa a-num num

Num

A-hoorepa hoorepa a-huh-hoorepa a-num num

Deba uba zat zat

A-hoorepa hoorepa a-huh-hoorepa a-num num

a-num

Hubba hubba zoot zoot

deba uba zat zat

HAH

A-hoorepa hoorepa a-huh-hoorepa a-num num

A-num

Hubba hubba zoot zoot

Deba uba zat zat a-num num

Hubba hubba zoot zoot

Duuh

Deba uba zat zat a-num num

A-hoorepa hoorepa a-huh-hoorepa a-num num

A-hoorepa hoorepa a-huh-hoorepa a-num num

HAH

A-num

Hubba hubba zoot zoot

Deba uba zat zat a-num num

Hubba hubba zoot zoot

Deba uba zat zat a-num num

A-hoorepa hoorepa a-huh-hoorepa a-num num

A-hoorepa hoorepa a-huh-hoorepa a-num num

HAH

Hubba hubba zoot zoot

Deba uba zat zat a-num num

HOH

Hubba hubba zoot zoot

Hubba hubba mo-re mo-re

Deba uba zat zat a-num num

A-hoorepa hoorepa a-huh-hoorepa a-num num

A-hoorepa hoorepa a-huh-hoorepa a-num num

A-num

(Thanks, Volodymyr.)

interturb

v. to disturb by interrupting

In late 1908 Douglas Mawson, Alastair Mackay, and Edgeworth David left Ernest Shackleton’s party in hopes of discovering the location of the South Magnetic Pole. On Dec. 11, while Mackay left the camp to reconnoiter, David prepared to sketch the mountains and Mawson retired into the tent to work on his camera equipment:

I was busy changing photographic plates in the only place where it could be done — inside the sleeping bag. … Soon after I had done up the bag, having got safely inside, I heard a voice from outside — a gentle voice — calling:

‘Mawson, Mawson.’

‘Hullo!’ said I.

‘Oh, you’re in the bag changing plates, are you?’

‘Yes, Professor.’

There was a silence for some time. Then I heard the Professor calling in a louder tone:

‘Mawson!’

I answered again. Well the Professor heard by the sound I was still in the bag, so he said:

‘Oh, still changing plates, are you?’

‘Yes.’

More silence for some time. After a minute, in a rather loud and anxious tone:

‘Mawson!’

I thought there was something up, but could not tell what he was after. I was getting rather tired of it and called out:

‘Hullo. What is it? What can I do?’

‘Well, Mawson, I am in a rather dangerous position. I am really hanging on by my fingers to the edge of a crevasse, and I don’t think I can hold on much longer. I shall have to trouble you to come out and assist me.’

I came out rather quicker than I can say. There was the Professor, just his head showing and hanging on to the edge of a dangerous crevasse.

David later explained, “I had scarcely gone more than six yards from the tent, when the lid of a crevasse suddenly collapsed under me. I only saved myself from going right down by throwing my arms out and staying myself on the snow lid on either side.”

Mawson helped him out, and David began his sketching. The party reached the pole in January.

antelucan

adj. before dawn

finitor

n. the horizon

flavescent

adj. turning pale yellow

day-peep

n. the first appearance of daylight; the earliest dawn

Eoan

adj. of or pertaining to the dawn; eastern

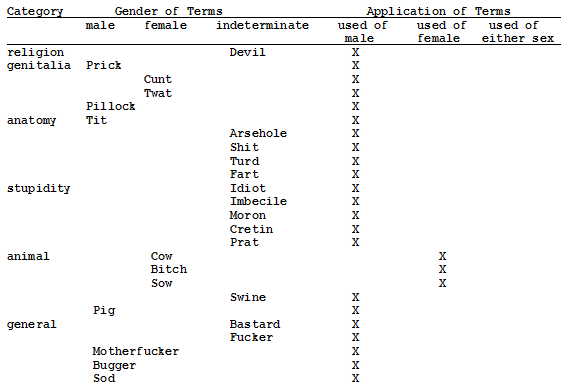

In An Encyclopedia of Swearing (2006), University of the Witwatersrand linguist Geoffrey Hughes notes that terms of vehement personal abuse seem to attach disproportionately to the male sex:

In his analysis, even terms derived from female anatomy are applied to men rather than women (at least in British usage). Terms such as bugger, motherfucker, and sod[omite] understandably derive from sexual role, but why are devil, fucker, moron, and cretin applied generally to men and not women?

“All the indeterminate terms, such as bastard, idiot, and shit, which should logically be ‘bisexual’ in application, are invariably applied only to males,” Hughes writes. (Also, strangely, there seems to be no vehement term of abuse that’s used freely of both sexes.) “However, the historical perspective shows one significant trend, namely that several of the terms, like bitch and sow, were first used of males (or of both sexes) and only later applied exclusively to women.”

When Canada introduced its 1-dollar coin in 1987, it became known as the “loonie” for the loon on its back.

When the Royal Canadian Mint introduced the 2-dollar coin in 1996, Canadians tried hard to find a comparable nickname. Though “toonie” or “twoonie” eventually won out, the list of failed suggestions included “doubloonie,” “doozie,” and the charming “moonie.”

Why moonie? Because the coin depicts the queen “with a bear behind.”

(Thanks, Ethan.)

zumbooruk

n. a small cannon fired from the back of a camel

Birder William Young notes that hobbyists who look for wild birds tend to identify species as much by their songs and calls as by their plumage. One way to memorize the calls is to translate them into familiar words and phrases. “Just as many people cannot remember lyrics to popular songs without singing the melody,” he writes, “many birders cannot remember bird songs and calls without thinking of mnemonic phrases.” Examples:

White-throated sparrow: Old Sam Peabody Peabody Peabody

Black-throated green warbler: trees, trees, murmuring trees

Black-throated blue warbler: I’m so la-zy

Olive-sided flycatcher: Quick, free beer!

White-eyed vireo: Pick up the beer check quick

Song sparrow: Maids maids maids pick up the tea kettle kettle kettle

American goldfinch: potato chip

Barred owl: Madame, who cooks for you?

Brown pigeon: Didja walk? Didja walk?

American robin: cheerily, cheer-up, cheerily

White-crowned sparrow: Poor JoJo missed his bus

Ovenbird: teacher, TEACHER, TEACHER

Red-eyed vireo: Here I am. Where are you?

Common yellowthroat: Which is it? Which is it? Which is it?

MacLeay’s honeyeater: a free TV

Common potoo: POO-or me, O, O, O, O

Inca dove: no hope

Brown quail: not faair, not faair

Little wattlebird: fetch the gun, fetch the gun

The California quail says Chicago, the long-tailed manakin says Toledo, and the rufous-browed peppershrike says I’M-A-RU-FOUS-PEP-PER-SHRIKE. “Once when I was staying at [birding author Graham Pizzey’s] home, a Willie-wagtail sang outside my bedroom window around 3 A.M. and seemed to say I’m trying to an-NOY you.” Young’s full article appears in the Winter 2003 issue of Verbatim.

guttatim

adv. drop by drop

supernaculum

adv. to the last drop

stillatitious

adj. falling in drops

quantulum

n. a small amount or portion

By Colorado classics teacher Jeremy Boor:

MP3, lyrics, and chords are on his website.