poecilonym

n. a synonym for synonym

poecilonym

n. a synonym for synonym

In the Ubang language of Nigeria, men and women speak different languages. They understand each other perfectly, but “It’s almost like two different lexicons,” says anthropologist Chi Chi Undie. “There are a lot of words that men and women share in common, then there are others which are totally different depending on your sex. They don’t sound alike, they don’t have the same letters, they are completely different words”:

| English | Male | Female |

| yam | itong | irui |

| clothing | nki | ariga |

| dog | abu | okwakwe |

| tree | kitchi | okweng |

| water | bamuie | amu |

| cup | nko | ogbala |

| bush | bibiang | déyirè |

| goat | ibue | obi |

Raised by their mothers and other women, boys grow up speaking the female language, but at age 10 they’re expected to switch, unbidden, to the male. “There is a stage the male will reach and he discovers he is not using his rightful language,” says Chief Oliver Ibang. “Nobody will tell him he should change to the male language. … When he starts speaking the men language, you know the maturity is coming into him.”

“God created Adam and Eve and they were Ubang people,” he says. He had planned to give two languages to each ethnic group, but after the giving two to the Ubang he realized there were not enough languages to continue. “So he stopped. That’s why Ubang has the benefit of two languages — we are different from other people in the world.”

Said Jerome K. Jerome to Ford Madox Ford,

“There’s something, old boy, that I’ve always abhorred:

When people address me and call me ‘Jerome’,

Are they being standoffish, or too much at home?”

Said Ford, “I agree; it’s the same thing with me.”

— William Cole

scrutator

n. a person who investigates

callid

adj. cunning or crafty

potpanion

n. a drinking companion

nocent

adj. guilty

In “The Adventure of the Abbey Grange,” a bottle of wine is two-thirds full and then half empty, without explanation.

In The New Annotated Sherlock Holmes, Leslie S. Klinger writes, “Perhaps Holmes poured some wine off to conduct an actual experiment, instead of simply imagining the result.” Or perhaps Holmes and Watson drank it themselves.

This is incredible. In 2005, mathematician Mike Keith took a 717-word section from the essay on Mount Fuji in Lafcadio Hearn’s 1898 Exotics and Retrospective and anagrammed it into nine 81-word poems, each inspired by an image from Hokusai’s famous series of landscape woodcuts, the Views of Mount Fuji.

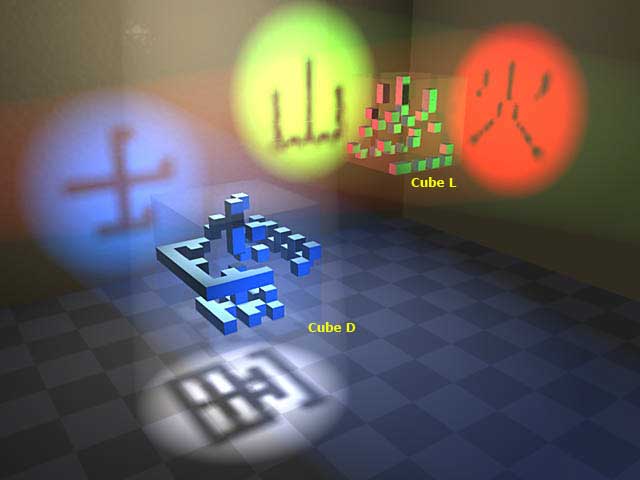

That’s not the most impressive part. Each anagrammed poem can be arranged into a 9 × 9 square, with one word in each cell. Stacking the nine grids produces a 9 × 9 × 9 cube. Make two of these cubes, and then:

Replace each “1” cell with solid wood and each “0” cell with transparent glass. Now suspend the two cubes in a room and shine beams of light from the top and right onto Cube D and from the front and right onto Cube L:

The shadows they cast form reasonable renderings of four Japanese kanji characters relevant to the anagram:

The red shadow is the symbol for fire.

The green shadow is the symbol for mountain.

Put together, these make the compound Kanji symbol (“fire-mountain”) for volcano.The white shadow is the symbol for wealth, pronounced FU

The blue shadow is the symbol for samurai, pronounced JI

Put together, these make the compound word Fuji, the name of the mountain.

See Keith’s other anagrams, including a 211,000-word recasting of Moby-Dick.

The “tombstone” (∎) used to denote the end of a proof was suggested by mathematician Paul Halmos. “The symbol is definitely not my invention,” he wrote. “It appeared in popular magazines (not mathematical ones) before I adopted it, but, once again, I seem to have introduced it into mathematics. It is the symbol that sometimes looks like ∎, and is used to indicate an end, usually the end of a proof. It is most frequently called the ‘tombstone’, but at least one generous author referred to it as the ‘halmos’.”

The group of mathematicians who wrote under the name Nicolas Bourbaki would include a “dangerous bend” symbol in the margin next to tricky or difficult passages, “to forewarn the reader against serious errors, where he risks falling.” Other writers have adopted the symbol, including computer scientist Donald Knuth, who included American-style road signs in his Metafont and TeX typesetting systems.

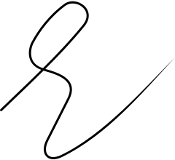

And teachers in the Netherlands use a distinctive “flourish of approval” when grading schoolwork to show that they have seen and agreed with a paragraph. The mark, which may have evolved from a hastily written g (for “good” [goed] or “seen” [gezien]), rarely appears outside the Netherlands and its former colonies.

The roots of the word helicopter are not heli and copter but helico and pter, from the Greek “helix” (spiral) and “pteron” (wing).

G.L.M. de Ponton’s 1861 British patent says, “The required ascensional motion is given to my aerostatical apparatus (which I intend denominating aeronef or helicoptere,) by means of two or more superposed horizontal helixes combined together.”

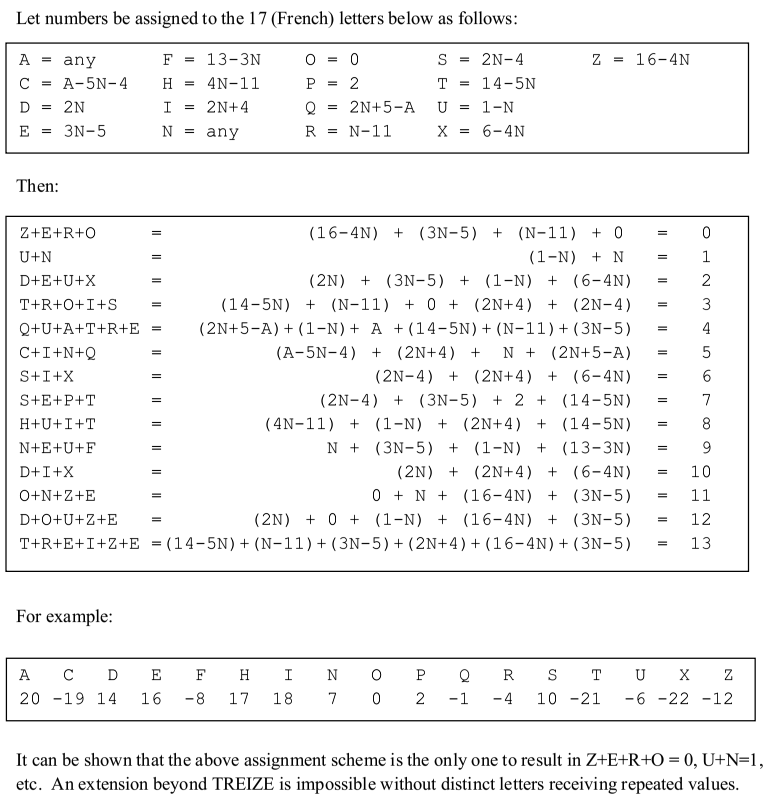

From Lee Sallows:

(Thanks, Lee!)

telepheme

n. a telephone message

telelogue

n. a conversation on the telephone

When I heard the learn’d astronomer,

When the proofs, the figures, were ranged in columns before me,

When I was shown the charts and diagrams, to add, divide, and measure them,

When I sitting heard the astronomer where he lectured with much applause in the lecture-room,

How soon unaccountable I became tired and sick,

Till rising and gliding out I wander’d off by myself,

In the mystical moist night-air, and from time to time,

Look’d up in perfect silence at the stars.

That’s Walt Whitman. In 2000, mathematician Mike Keith noted a similar idea in Psalm 19:1-6:

The heavens declare the glory of God;

And the firmament sheweth his handywork.

Day unto day uttereth speech,

And night unto night sheweth knowledge.

There is no speech nor language,

Where their voice is not heard.

Their line is gone out through all the earth,

And their words to the end of the world.

In them hath he set a tabernacle for the sun,

Which is as a bridegroom coming out of his chamber,

And rejoiceth as a strong man to run a race.

His going forth is from the end of the heaven,

And his circuit unto the ends of it:

And there is nothing hid from the heat thereof.

So he married them by rearranging the psalm’s letters:

When I had listened to the erudite astronomer,

When his high thoughts were arranged and charted before me,

When I was shown the length and breadth and height of it,

The Earth, the horned Moon, the chariot of fire,

The hundredth flight of the shuttle through heavyish air,

How soon, mysteriously, I became sad and sick,

Had to wander out, ousted, charging through the forest,

Joining the sure chaos here in a foreign heath,

Having forgotten the vocation of the learned man,

And in the mystic clearing, once more looked up

In perfect silence at the sermon in the stars.

(Michael Keith, “Anagramming the Bible,” Word Ways 33:3 [August 2000], 180-185.)